Business corporations long ago rejected the idea of unaccountable directors running firms with only their consciences to keep them in check. Yet unaccountable boards are the norm in the nonprofit sector. This need not be the case. The laws of all fifty states and the District of Columbia provide a template for accountability in nonprofit governance: membership statutes. These statutes define the roles and responsibilities of nonprofit members, usually by explicit or implicit reference to shareholders of business corporations. Membership need not be restricted to mutual-benefit organizations, but instead can be an oversight tool for public charities and other nonprofits. This Comment conducts a fifty-one-jurisdiction survey of nonprofit membership statutes, concluding that while jurisdictions differ in how they treat members, they cohere around the idea of members as monitors whose rights can be selected from a flexible menu of statutory provisions. Statutory law vests members with the information, influence, and arguably the incentive to be effective nonprofit principals, providing the voluntary sector with a level of accountability it currently lacks.

Introduction

In 2017, Snap—the company behind the social media platform Snapchat—made a controversial decision to issue shares with no voting rights, essentially vesting control in a small and unaccountable group of directors and early investors. 1 James Rufus Koren & Paresh Dave, Snap Won’t Give Shareholders Voting Rights. For That, It’s Being Shunned by a Major Stock Index, L.A. Times (July 27, 2017), https://www.latimes.com/business/la-fi-snap-russell-indices-20170727-story.html (on file with the Columbia Law Review) (last updated July 28, 2017). The criticism was immediate. After institutional investors complained, major stock indexes dropped Snap over its stock structure. 2 See id. (reporting that the Russell 3000 delisted Snap over its stock structure). Snap was also delisted by the S&P 500. Anita Balakrishnan, Snap Is Falling Again as Wall Street Worries About the Company’s Corporate Structure, CNBC (Aug. 1, 2017), https://www.cnbc.com/2017/08/01/snapchat-excluded-from-sp-500-what-does-it-mean.html [https://perma.cc/NRW6-DUCK]. Commentators opined that this structure—board members who basically answer to nobody—undermines accountability and shareholder democracy, allowing inefficiencies to breed. 3 See, e.g., Ken Bertsch, Council of Institutional Investors, Snap and the Rise of No-Vote Common Shares, Harv. L. Sch. F. on Corp. Governance (May 26, 2017), https://corpgov.law.harvard.edu/2017/05/26/snap-and-the-rise-of-no-vote-common-shares [https://perma.cc/K33A-U7YF]. Yet this structure is the norm in nonprofit governance.

A nonprofit is an agent in search of a principal. 4 This problem was articulated most eloquently by Professor Evelyn Brody: “[I]n most nonprofits there is no clear category of principals. Under law, the nonprofit firm is not the agent of a particular donor or client or beneficiary. As a result, most state nonprofit laws, perhaps without intending to, create agents without principals.” Evelyn Brody, Agents Without Principals: The Economic Convergence of the Nonprofit and For-Profit Organizational Forms, 40 N.Y. L. Sch. L. Rev. 457, 465 (1996) [hereinafter Brody, Agents] (footnote omitted). Directors answer to nobody: They have no masters and no constituents. 5 As one corporate law scholar put it, “No one can threaten to oust NPO [nonprofit organization] directors; so long as they obey the law, they need only satisfy themselves.” George W. Dent, Jr., Corporate Governance Without Shareholders: A Cautionary Lesson from Non-Profit Organizations, 39 Del. J. Corp. L. 93, 98 (2014). They have only the (vanishingly rare) threat of regulatory enforcement to keep them in check. 6 See Robert L. Gray, State Attorney General—Guardian of Public Charities, 14 Clev.-Marshall L. Rev. 236, 238 (1965) (noting that while states have endowed state attorneys general with the authority to enforce the fiduciary duties of nonprofit directors, “they have not always provided the revenue necessary to hire the human machinery needed”) ; see also Cindy M. Lott, Elizabeth T. Boris, Karin Kunstler Goldman, Belinda J. Johns, Marcus Gaddy & Maura Farrell, State Regulation and Enforcement in the Charitable Sector 33 (Sept. 2016), https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/84161/2000925-State-Regulation-and-Enforcement-in-the-Charitable-Sector.pdf [https://perma.cc/3Z7F-9YXM] (surveying state enforcement regimes and concluding that while government oversight is “more robust than people in the charitable sector assume,” charities generally rely on stakeholders for oversight and “[s]taffing for oversight of the US charitable sector has not grown with the charitable sector”). Were directors perfectly loyal and competent, this status quo would be unproblematic. In fact, they are often disengaged, unprofessional, and ineffective. 7 See Dent, supra note 5, at 98 (“[A]ccording to a virtually unanimous consensus of experts . . . [nonprofit organization] directors are generally uninformed and disengaged.”). One treatise commented that in the nonprofit sector, the word “board” has become synonymous with the term “troubled board.” 8 See Richard P. Chait, William P. Ryan & Barbara E. Taylor, Governance as Leadership: Reframing the Work of Nonprofit Boards 11 (2005). “When we describe boards it is often to distinguish one bad one from another: Letterhead board or micromanaging board? Founder’s board or rubber-stamp board?” Id. When boards underperform, a supervening authority rarely is on hand to punish or replace them. 9 See supra note 5. This need not be the case.

The laws in all fifty states and the District of Columbia provide an authority to keep directors in check: members. 10 See infra Appendix. Typically, the only nonprofits with members are mutual-benefit organizations: nonprofits that serve well-defined groups of member-funders, like fraternal orders and country clubs. 11 Mutual-benefit organizations aim to serve their members, who in turn generally pay for those services. Geoffrey A. Manne, Agency Costs and the Oversight of Charitable Organizations, 1999 Wis. L. Rev. 227, 242. “Member control is more common in the mutual nonprofit, such as a labor organization, social club, or business league. Most charities and social welfare organizations, by contrast, have no members, or have members only in the ceremonial sense.” Evelyn Brody, Entrance, Voice, and Exit: The Constitutional Bounds of the Right of Association, 35 U.C. Davis L. Rev. 821, 832 (2002). However, the legal framework for membership is much broader. Membership need not be restricted to mutual-benefit organizations but can be deployed to create a class of principals that keep nonprofit directors and officers accountable. Unlike existing nonprofit stakeholders, members are endowed by law with the information and the influence to be competent nonprofit principals. A fifty-one-jurisdiction analysis of nonprofit membership statutes shows how state laws vest members with the rights and powers necessary to effectively govern nonprofits.

This Comment proceeds in three parts. Part I shows how nonprofits presently suffer from a lack of oversight, as existing stakeholders lack either the means or incentive to act as competent principals. Part II uses a fifty-one-jurisdiction survey to show that the predominant model for nonprofit members is one of permissive rights—analogous to shareholders in a business corporation—that vests members with the powers necessary to oversee nonprofit organizations. Part III argues that members have the information and influence needed to act as effective monitors of nonprofit organizations and need only be incentivized to do the dirty work of governing. In addition to comprehensively surveying nonprofit statutes for the first time, 12 The closest that any other researcher has come to compiling such a data set would be the Independent Sector’s review of state nonprofit laws. See State Laws for Charitable Organizations, Indep. Sector (Dec. 20, 2016), https://independentsector.org/resource/statelaws [https://perma.cc/6MCC-QRTS]. However, Independent Sector’s review focuses on “Formation, Elections, Operation, and Dissolution; Duties, Indemnification, and Interested Transactions; Notable Departures from Federal Law; General; Model Acts; and Tax Exemptions,” and does not address membership. See id. this Comment provides a template for understanding nonprofit membership, its potential and its pitfalls.

I. Agents in Search of Principals

Although the language of agency costs is typically reserved for business corporations, it serves to elucidate the nonprofit dilemma. Agency costs are the costs engendered by the fact that agents almost always have disparate incentives from their principals. 13 In a seminal article, Professors Michael Jensen and William Meckling defined agency costs as an intrinsic feature of the firm: “In most agency relationships the principal and the agent will incur positive monitoring and bonding costs (non-pecuniary as well as pecuniary), and in addition there will be some divergence between the agent’s decisions and those decisions which would maximize the welfare of the principal.” Michael C. Jensen & William H. Meckling, Theory of the Firm: Managerial Behavior, Agency Costs and Ownership Structure, 3 J. Fin. Econ. 305, 308 (1976) (footnote omitted). Shareholders would prefer for executives to energetically pursue profit; executives would prefer to play golf and take long afternoon naps. At nonprofits, agency costs are exacerbated by the fact that it is not entirely clear who the principal actually is. 14 Manne, supra note 11, at 230–31 (“[N]onprofit firms are not owned, at least not in the usual legal sense. As a result, they cannot successfully rely on their residual claimants to overcome the agency costs inherent in the corporate (or trust) form . . . .” (footnote omitted)). If nonprofit directors had a constituency to satisfy—a constituency with the power to remove and replace them for misfeasance or dereliction—they would likely be more energetic monitors of executive and employee performance. 15 At minimum, installing a principal class would have the benefit of introspection posited by Brody: “Having to account for one’s actions requires one to think about them harder: to be more analytic, to take longer to reach a decision, and to devote more resources to the process.” See Brody, Agents, supra note 4, at 517. As Brody notes, the requirement of reflection and deliberation engenders both costs and benefits. See id.

In practice, nonprofits resemble the least accountable version of the business corporation. Before the 1980s, corporations were mostly owned by retail investors, whose numbers, geographic dispersion, and lack of sophistication made it impossible for them to police director and officer misconduct. 16 See Marcel Kahan & Edward Rock, Embattled CEOs, 88 Tex. L. Rev. 987, 995–98 (2010) (documenting the shift from individual to institutional ownership). Scholars bemoaned this model—the so-called Berle–Means corporation—as excessively prone to agency costs. 17 Bernard S. Black, Agents Watching Agents: The Promise of Institutional Investor Voice, 39 UCLA L. Rev. 811, 813 (1992) (noting that the Berle–Means paradigm was “under attack” by critics who argue that, under the dispersed-shareholder model, “shareholder passivity is inevitable” due to collective action problems). Thus, they celebrated the rise of institutional investors—large financial institutions with the capacity and know-how to monitor corporate boards and reduce agency costs. 18 See id. (arguing that “[l]arge institutions could overcome the incentives for passivity created by fractional ownership”). Nonprofits without members can be thought of as Berle–Means corporations. 19 See Brody, Agents, supra note 4, at 536 (arguing that the differences between nonprofits and business corporations “are more of degree than of kind”). Whereas institutional investors retired the Berle–Means model for business corporations, nonprofit directors typically answer only to their own consciences, meaning they are less efficient than they otherwise would be. 20 See supra notes 5–8 and accompanying text.

Whatever its source, inefficiency appears rife in the nonprofit sector. One commentator noted that the nonprofit sector “seems to drift, moving blindly and without discipline . . . . It often seems listless, sluggish, passive, and defensive.” 21 Richard C. Cornuelle, Reclaiming the American Dream: The Role of Private Individuals and Voluntary Associations 52 (Routledge 2017). At least one reason for this existential malaise is a lack of constituent control to keep nonprofit employees motivated. 22 Dennis R. Young, If Not for Profit, for What? 115 (2013) (noting the “large margin for discretionary behavior” for nonprofit professionals and attributing it to “[t]he relatively indirect and part-time control exerted by constituent groups”). The problem is not a lack of potential principals—beneficiaries, donors, and the public could potentially fill the void—but rather, a lack of suitable ones. None of these constituencies seems to be ideal, and even if they were, none is vested with the power and capacity to serve as principals.

Professor David Schizer puts forward a model for evaluating nonprofit principals along “the three I’s”: incentive, influence, and information. 23 David M. Schizer, Enhancing Efficiency at Nonprofits with Analysis and Disclosure, 11 Colum. J. Tax. L. 76, 92 (2020). Monitors can be fully effective only if they have all three characteristics: the incentive to invest time and effort into the job of overseeing the nonprofit, the influence to get managers to act in accordance with their agenda, and the incentive to invest the time and energy to wield that influence. 24 Id. Government regulators have influence over nonprofits via their ability to bring enforcement actions, but they rarely have the incentive or information necessary to do so, instead favoring a “hands off” approach. 25 Id. at 93. In any case, they often lack the person power to comprehensively monitor the nonprofit sector. 26 A survey of all U.S. states and territories found that 31% of jurisdictions have one or fewer full-time enforcement employees overseeing all charities; only 19% had ten or more. Lott, supra note 6, at 8 tbl.1. A charity’s beneficiaries often have the incentive and information to oversee its activities, but the law does not grant them standing to enforce their agenda. 27 Schizer, supra note 23 at 97–99. In one notable exception to the rule that donors do not have standing to enforce fiduciary duties at nonprofits, the D.C. District Court held that a group of patients had standing to sue a nonprofit hospital for breaches of loyalty and trust based on their “special interest.” See Stern v. Lucy Webb Hayes Nat’l Training Sch. for Deaconesses & Missionaries, 367 F. Supp. 536, 540 (D.D.C. 1973), supplemented, 381 F. Supp. 1003 (D.D.C. 1974). This rare court victory for donors sparked some enthusiasm over beneficiary empowerment and standing. See, e.g., Sara R. Kusiak, Note, The Case for A.U. (Accountable Universities): Enforcing University Administrator Fiduciary Duties Through Student Derivative Suits, 56 Am. U. L. Rev. 129, 161 (2006) (noting the response to Stern and using its holding to argue for a cause of action for students to bring derivative suits to enforce breaches of care at universities). However, other courts have looked at Stern and its holding with skepticism. See O’Donnell v. Sardegna, 646 A.2d 398, 410 (Md. 1994) (rejecting the logic in Stern). Even other judges in the District of D.C. itself seem to have had trouble with the Stern precedent. See Christiansen v. Nat’l Sav. & Tr. Co., 683 F.2d 520, 527 (D.C. Cir. 1982) (noting that the court below “had considerable difficulty with his colleague’s decision in the Stern case”). The so-called “special interest” doctrine of beneficiary standing seems to have gained limited acceptance, leaving beneficiaries with few legal rights over the nonprofits that serve them. See Mary Grace Blasko, Curt S. Crossley & David Lloyd, Standing to Sue in the Charitable Sector, 28 U.S.F. L. Rev. 37, 42–44 (1993). Lastly, donors generally care about how their money is spent, and so they have an incentive to encourage nonprofit efficiency. 28 Schizer, supra note 23, at 101. However, their incentives can be various and conflicting, preventing them from acting as a unit to oversee a nonprofit’s activity. 29 Id. at 101–02; see also Manne, supra note 11, at 236 (“[W]idely-dispersed donors and beneficiaries face severe problems of collective action in monitoring, along with legally-attenuated property rights and questionable standing in the courts.”). Moreover, while donors can use the prospect of future donations to wield influence over a nonprofit, 30 See Schizer, supra note 23, at 106. they do not have any formal legal authority to intercede in its affairs. 31 See Brody, Agents, supra note 4, at 535 (noting that “as a legal matter . . . donors [do not] maintain control over contributed amounts”). Finally, the information they receive can be fragmentary and unreliable. 32 See Schizer, supra note 23, 103–06.

That leaves the board of directors. 33 Id. at 98. Legally, boards are the self-accountable principal of the nonprofit form: They are the fiduciaries entrusted with oversight and ultimate discretion over its operations. 34 See Dent, supra note 5, at 97. In practice, however, they are deeply problematic as principals. 35 See Chait et al., supra note 8, at 11 (“The board appears to be an unreliable instrument for ensuring accountability . . . . Behind every scandal or organizational collapse is a board (often one with distinguished members) asleep at the switch.”). Often, they are disengaged altogether: A study of more than 5,000 American nonprofits found that only slim majorities of boards engage in financial oversight or organizational policy-setting. 36 See Francie Ostrower, The Urb. Inst., Nonprofit Governance in the United States: Findings on Performance and Accountability from the First National Representative Study 12 (2007), https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/46516/411479-Nonprofit-Governance-in-the-United-States.PDF [https://perma.cc/H94K-ZHDT] (noting that “[o]nly a minority of boards were very active when it came to” activities such as monitoring the organization’s performance (32%) and planning for the future (44%)). The study concluded, “Substantial percentages of boards are simply not actively engaged in various basic governance activities.” 37 Id. at 22. As volunteers, directors have little intrinsic motivation to put in the hard work of nonprofit governance, meaning their commitment is sometimes sporadic and half-hearted. 38 See Schizer, supra note 23, at 99. In sum, boards have influence over nonprofits and the authority to obtain the necessary information, but they vary in the extent to which they are willing to wield that influence and authority. 39 See id. at 98–101. As Schizer puts it, “[S]ome board members are a solution to agency costs, while others are part of the problem.” 40 Id. at 101.

If boards have the means to ameliorate nonprofit inefficiency, the best solution may be to incentivize them to do so. Part III argues that an empowered membership can do just that. However, the next Part outlines the institution of membership as it exists in state law to examine its contours and limits. A fifty-one-jurisdiction review of state membership statutes shows that, like shareholders, members are purpose-built to act as effective principals by ensuring that board members do the job they are entrusted with.

II. Members as “Shareholders”

Just as shareholders need not be (and rarely are) the sole beneficiaries of a corporation’s services, members need not be the same group of people that benefits from a nonprofit’s services, as in a country club or church. Instead, members can act as the constituent group with final authority over the nonprofit—its principals. Indeed, states have crafted membership around an analogy to the shareholders of business corporations, providing members with the tools they need to do the dirty work of nonprofit governance.

This Comment conducts a first-ever fifty-one-jurisdiction survey of nonprofit membership statutes, evaluating state codes according to the powers and rights they grant to members. 41 See infra Appendix. State statutes typically create a flexible menu of member rights that can be defined in a nonprofit’s governing documents. In general, members are defined more or less as the nonprofit equivalent of shareholders, meaning they are the ideal vehicle to provide oversight to the nonprofit form. This Part relays the results of the statutory survey and outlines the contours of nonprofit membership.

The most influential modern attempt to codify the powers and rights of nonprofits—the Model Nonprofit Corporations Act (MNCA)—explicitly fashioned the rights of members around those of shareholders, 42 See 1 William W. Bassett, W. Cole Durham & Robert Smith, Religious Organizations and the Law § 9:8 (2d ed. 2017) (noting the influence of the MNCA on nonprofit law). In 1988, the ABA revised the original 1952 Model Act to split nonprofits into different categories. Id. To the extent that these categories had different membership rights, the revised Act diverged from the shareholder model, which provides a single template that all business corporations can use. See John Armour, Henry Hansmann & Reinier Kraakman, The Essential Elements of Corporate Law 3–4 (Eur. Corp. Governance Inst., Working Paper No. 134/2009, 2009), https://papers.ssrn.com/ abstract_id=1436551 (on file with the Columbia Law Review) (noting that the core function of corporation law is to provide a common structure for business enterprises with several key attributes). However, in 2008, the ABA abandoned the taxonomy and moved back to a single set of rules, thus hewing closer to the shareholder model. See Bassett et al., supra, § 9:8. Most states have followed suit, see infra Appendix, although California is a notable holdout, separating organizations into public-benefit and mutual-benefit corporations. Compare Cal. Corp. Code §§ 5110–5111 (2020) (pertaining to charities), with Cal. Corp. Code §§ 7710–7711 (2020) (pertaining to mutual-benefit organizations), and Cal Corp. Code § 9110–9111 (2020) (pertaining to religious nonprofits). Several states, however, make some exceptions for the needs of religious organizations. See, e.g., Idaho Code § 30-1102 (2020) (allowing religious nonprofits to abolish right of members to inspect the organization’s books and records). and, for the most part, states have adopted the members-as-shareholders analogy, either explicitly or implicitly. The few states that adopt an explicit analogy to shareholders tend to forgo specific nonprofit corporation acts, instead defining nonprofits as a species of nonstock corporations. So, for instance, in Delaware, a nonprofit is identical to a business corporation, except that “[a]ll references [in the Code] to stockholders of the corporation shall be deemed to refer to members of the corporation.” 43 Del. Code tit. 8, § 114 (2020). Kansas, Maryland, and Oklahoma take the same approach, with a Rosetta Stone statute translating between stock and nonstock corporations. See Kan. Stat. Ann. § 17-6014 (West 2020); Md. Code Ann., Corps. & Ass’ns § 5-201 (West 2020); Okla. Stat. tit. 18, § 1004.1 (2020). More common, however, are states that maintain separate nonprofit codes but define discrete membership rights that roughly mirror those of shareholders. 44 See infra Appendix. Thus, a typical statute is a Kentucky law providing that a nonprofit can set in its bylaws “the manner of election or appointment and the qualifications and rights of the members.” 45 Ky. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 273.187 (West 2020).

To be sure, statutes vary significantly across states. 46 See infra Appendix; see also infra text accompanying notes 47–50. For instance, while nonprofit members in New York are prohibited by law from transferring their membership, Nevada and Michigan allow nonprofits to provide for the transfer of membership in their governing documents. 47 Compare N.Y. Not-for-Profit Corp. Law § 501 (McKinney 2020) (making membership nontransferable), with Mich. Comp. Laws Ann. § 450-2303 (West 2020) (allowing nonprofits to waive inalienability of membership in their governing documents), and Nev. Rev. Stat. § 82.236 (2019) (same). Louisiana even permits nonprofits to issue capital stock. 48 See La. Stat. Ann. § 12:209 (2020) (“A corporation which is not permitted to distribute its net assets to its members upon dissolution may be organized either on a stock basis or on a non-stock basis.”). States differ in their broader approach as well as in the particulars. New Hampshire allows a nonprofit’s incorporators to vest members with whatever rights and privileges they might dream up, 49 New Hampshire maintains an exceedingly spare body of nonprofit statutes, see N.H. Rev. Stat. Ann. §§ 292:2–292:6-B (2020) (comprising essentially all the general statutory provisions governing nonprofits), the heart of which is N.H. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 292:6, providing that a nonprofit’s bylaws may contain “any provisions for the regulation and management of the affairs of the corporation not inconsistent with the laws of the state or the articles of agreement, including provisions for issuance and reacquisition of membership certificates.” One might hesitate to set up a nonprofit in New Hampshire if one seeks clear guidance from the law. while California provides a strict, mandatory set of rights that cannot be waived in an organization’s bylaws or articles of incorporations. 50 See infra Appendix.

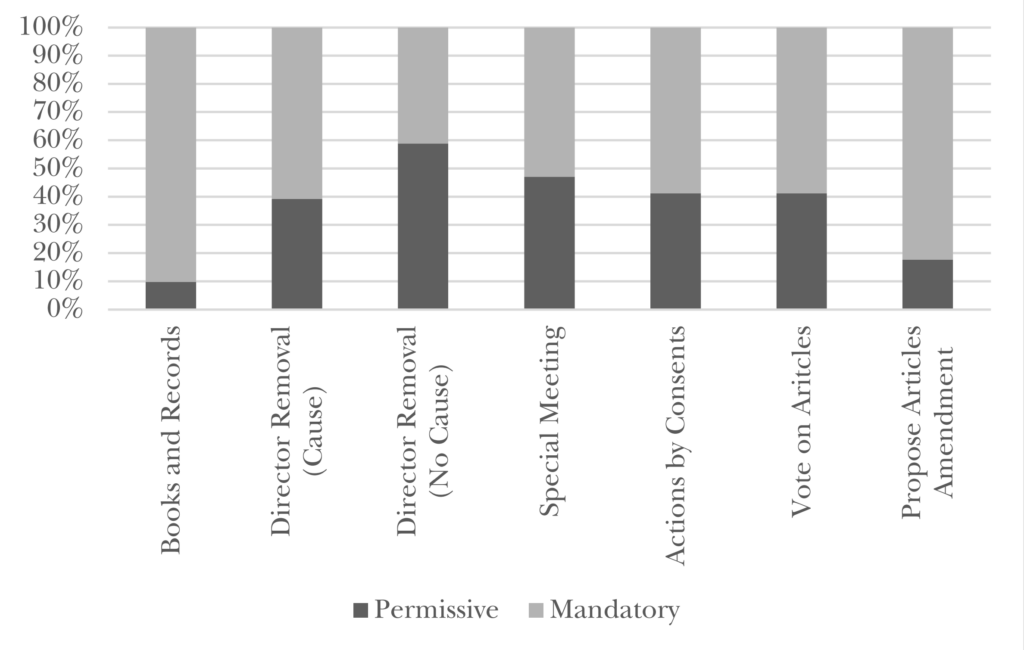

In general, however, a survey of nonprofit statutes shows that incorporators generally have the power, within limits, to define membership across a set of rights and powers. The survey looked at seven different types of member rights and powers: (1) the right to inspect a nonprofit’s books and records, (2) the power to remove directors with or (3) without cause, 51 Director removal statutes sometimes distinguish between members capable of voting and those not capable of voting. For instance, N.D. Cent. Code § 10-33-36 (2019) provides that directors are removable “[i]f there is a member with voting rights.” This survey assumed members were vested with some voting powers and asked whether members so vested were empowered to remove directors. Additionally, some statutes specify that directors can be removed by members only if they were elected by members. See, e.g., S.C. Code Ann. § 33-31-808 (2020). The survey presumed that incorporators made an initial choice to have some number of elective and/or appointive directors. For this reason, it only focused on members’ ability to depose directors they elected in the first place. Functionally, then, the results below presume and thus ignore the caveat that members in some states can only remove directors they elect. It is worth noting, however, that certain states occupy the opposite end of the removability spectrum, providing that directors can always be removed by members, even if they were not elected by members. So, for example, in California “any or all directors may be removed without cause” by the members. Cal. Corp. Code § 5222 (2020). (4) the power to call a special meeting, (5) the right to take action by written consent, 52 “Written consent” refers to the power to take an action without a meeting provided that a certain proportion of members—or all of them—assent in writing to the action. See, e.g., Minn. Stat. § 317A.445 (2019) (“An action required or permitted to be taken at a meeting of the members may be taken without a meeting by written action signed, or consented to by authenticated electronic communication, by all of the members entitled to vote on that action.”). and (6) the right to vote on or (7) propose amendments to the articles of incorporation. Further, the survey defined these rights as either permissive, meaning they can be defined or waived in a nonprofit’s governing documents, or mandatory, meaning that state law provides that members either do or do not have these rights. 53 Since California provides a taxonomy of different nonprofits with different rights and rules, see supra note 42, the survey looked exclusively at the laws governing public-benefit nonprofits, which are the main focus of this Comment. The results can be seen in Figure 1.

Again, the results vary broadly by state. California, for instance, makes all these rights mandatory, while Utah allows nonprofits to waive them all, with the exception of books and records inspection. 54 See infra Appendix. Broad patterns emerge for each right. Most jurisdictions (forty-six) make books and records inspection mandatory, 55 See infra Appendix. Two states condition books and records inspection on the request of a certain number or proportion of members. See Md. Code Ann., Corps. & Ass’ns § 2-513 (West 2020) (restricting inspection to demands by 5% of any class); Nev. Rev. Stat. § 82.186 (2019) (restricting inspection to demands by 15% of members). As with the removal statutes, see supra note 51, the survey assumed that some members were empowered with some voting rights. Thus, the Maine books-and-records statute, which provides that “[a]ll books and records of a corporation may be inspected by any officer, director or voting member,” was considered to have a mandatory right of inspection. Me. Rev. Stat. Ann. tit. 13-B, § 715 (2020) (emphasis added). and most (twenty-seven) bar members from proposing amendments to the articles of incorporation. 56 See infra Appendix. Generally, the states that prohibit members from proposing amendments do so by mandating a strict procedure by which directors must adopt a resolution recommending an amendment before members can vote on it. See, e.g., Tex. Bus. Orgs. Code § 22.105 (2019). This method is not uncommon for business organizations. See, e.g., Del. Code tit. 8, § 242 (2020). Other jurisdictions provide that a certain proportion of members can propose amendments. See, e.g., D.C. Code § 29-408.03 (2020) (providing that, by default, 10% of members can propose an amendment to the articles). Notably, another fifteen jurisdictions mandate that members must be allowed to propose amendments, bringing the total number of mandatory jurisdictions for this category to forty-two. 57 See infra Appendix. Apart from these two categories, however, jurisdictions are narrowly split between making rights permissive or mandatory. Most (thirty) require that members be allowed to remove directors they elect, 58 That is, most require that elected directors be removable for cause. See infra Appendix. A minority (nineteen) provide for mandatory director removal with or without cause. See infra Appendix. To reiterate an earlier caveat, this statement applies to nonprofits whose membership has some voting power in the first place. See supra note 51. And, to add a new caveat, some states provide that directors are removable unless elected to a classified board—that is, a board with multiple classes of directors elected in different years. See, e.g., Me. Rev. Stat. Ann. tit. 13-B, § 704. Finally, some states restrict the removal of directors elected cumulatively (a system of voting that allows minorities to elect directors by pooling their votes into one election). See, e.g., Va. Code § 13.1-860 (2020). although fewer than half of those jurisdictions (thirteen) require that members be able to remove any director, whether elected or appointed. 59 See infra Appendix; see also, e.g., Cal. Corp. Code § 5222 (2020) (providing that “any or all directors may be removed without cause”). Additionally, twenty-nine jurisdictions require that members vote on proposals to amend the articles of incorporation. 60 See infra Appendix. Once again, the survey presumes that members have some voting rights; so, for example, a statute that specifies that an articles amendment must be approved “by the members with voting rights” is considered to be a mandatory approach to the articles amendment power. See N.D. Cent. Code § 10-33-15 (2019). By contrast, New Mexico, for instance, provides that the members need only be consulted about an articles amendment “if there are members entitled to vote thereon.” N.M. Stat. Ann. § 53-8-36 (West 2020). This statute implies that members—who otherwise have the power to vote—may be specifically disentitled from voting on the articles amendment; it would thus be considered a permissive statute. A small majority (twenty-eight) take a permissive approach to the power to act by consents, while a slim minority (twenty-four) make the power to call special meetings permissive. 61 See infra Appendix. As to the latter, the balance (twenty-seven) provide that some specified percentage of members have a nonwaivable right to call a special meeting. See infra Appendix. Finally, just as a split emerges among jurisdictions as to which rights are mandatory and permissive, within jurisdictions, most exist on a spectrum between California and Utah—between all mandatory rights and all permissive rights, with some combination of each. 62 See infra Appendix.

Figure 1: Rights of Members Across Fifty-One Jurisdictions

Moreover, nonprofits that prefer a more flexible approach than their home state offers generally can incorporate outside the state where they are headquartered, just like business corporations. 63 Cf. J.J. Harwayne Leitner & Leanne C. McGrory, The “Delaware Advantage” Applies to Nonprofits, Too, Bus. L. Today, Nov. 2016, at 1, https://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/publications/blt/2016/11/full-issue-201611.pdf [https://perma.cc/5YZD-H7EJ] (suggesting, from a practitioner’s point of view, that nonprofits consider incorporating in Delaware). Of course, there are costs associated with foreign registration, such as extra taxes and the cost of maintaining an address. 64 See id. (noting “the requirement of maintaining a registered agent in Delaware and the likelihood of having to pay fees in both Delaware and the state of domicile” as potential costs of Delaware incorporation). And there are factors other than membership rights to consider, such as the startup costs of incorporating and the level of scrutiny from state attorneys general. 65 See id. at 1–2 (“Incorporation in Delaware is quick and painless, whereas the New York State Department of State regularly rejects certificates of incorporation, causing delays in incorporation as well as increased legal fees . . . .”). However, a California nonprofit of sufficient size and sophistication, for instance, seeking flexibility that California fails to provide can look beyond its borders to states like Utah or Hawaii that define membership flexibly. 66 See infra Appendix.

This Part has sought to characterize the rights of members across fifty-one jurisdictions. States provide a mix of mandatory and permissive rights that vary from strict (California) to lax (Utah). 67 See id. Books and records inspection is typically available while the power to propose amendments typically is not. 68 See supra notes 55–60 and accompanying text. In general, though, states provide a menu of member rights from which nonprofits can pick and choose. The following Part demonstrates how the complex of rights available to nonprofit members make them ideal nonprofit principals.

III. The Membership Solution

Part I argues that nonprofits are agents in search of principals, and that self-perpetuating boards contribute to agency costs and widespread inefficiency, while Part II outlines the rights and powers of a particular class of principals: members. This Part argues that members, as defined by state statutes, provide a principal that—at least in theory—has the means to effectively police board behavior. Returning to the model Part I sets out, the law provides members with the influence and information needed to be effective monitors. As to incentives, while members potentially face the same pitfalls as volunteer directors, membership can be structured to encourage participation and buy-in. Furthermore, even without such mechanisms, members serve as a natural check on the power of otherwise self-perpetuating directors.

A. Influence

Membership comes with a baseline of influence: For example, in at least forty jurisdictions, a member can take a director or officer to court for a breach of loyalty or care. 69 See infra Appendix (showing that at least forty states allow derivative suits); see also, e.g., Utah Code § 16-6a-612 (2020) (providing that members and directors of nonprofits can bring derivative actions in the name of the nonprofit). As Part II discusses above, most states allow members mandatory books-and-records inspection rights. See supra Part II. Apart from these few mandatory rights, however, a member’s influence largely depends on what is in an organization’s bylaws. 70 See supra Part II. So, for example, a fully empowered membership would be able to elect or remove all or most board members, vote on amendments to the articles of incorporation, and approve major transactions. 71 See infra Appendix.

However, empowering members may be a costly proposition. State laws generally provide that members—even those with minimal rights—must meet regularly. 72 See, e.g., 15 Pa. Cons. Stat. § 5755 (2020). Additional rights come with additional costs. For instance, where members can put forward a proposal to amend the articles of incorporation, corporate resources must be expended analyzing and responding to proposals. 73 Cf. Procedural Requirements and Resubmission Thresholds Under Exchange Act Rule 14a–8, 84 Fed. Reg. 66,458, 66,459 (proposed Dec. 4, 2019) (to be codified at 17 C.F.R. pt. 240) (noting that shareholder proposals “draw upon company resources and . . . command the time and attention of other shareholders”). A small nonprofit might not be able to handle this type of expenses. Thus, nonprofit membership statutes supply the ideal principal not because they fully empower members by default, but because they allow nonprofits to determine just how much influence members will have. 74 Professors Zohar Goshen and Richard Squire supply the analogous argument in the context of business corporations, arguing that agency costs are not the sole factor in analyzing shareholder empowerment. Rather, shareholders introduce costs of their own—“principal costs”—so that the relevant analysis is “control costs,” the sum of agency costs and principal costs. Zohar Goshen & Richard Squire, Principal Costs: A New Theory for Corporate Law and Governance, 117 Colum. L. Rev. 767, 770 (2017). So, rather than seeking to minimize agency costs, corporations should seek to minimize control costs. Id. Here, then, one can think of nonprofit control costs as consisting of “membership costs” and agency costs. By minimizing the sum of these two quantities, nonprofits can achieve efficient corporate governance.

B. Information

Members are legally entitled to inspect a nonprofit’s records, including its finances. 75 See, e.g., Iowa Code § 504.1611 (2020) (“Except as provided . . . a corporation upon written demand from a member shall furnish that member the corporation’s latest annual financial statements . . . .”). Further, if a nonprofit refuses to turn over records, members generally can demand those records in summary proceedings. 76 See, e.g., Ariz. Rev. Stat. § 10-11604 (2020) (“If a corporation does not allow a member . . . to inspect and copy any records required . . . to be available for inspection, the court . . . may summarily order inspection and copying of the records demanded at the corporation’s expense . . . .”). While inquisitive donors are likely to have reports tailored to them—providing a selective picture of the nonprofit’s operations 77 See Schizer, supra note 23, at 104. —statutes broadly give members access to all of the firm’s “accounting books and records.” 78 Cal. Corp. Code § 6333 (2020). At least in theory, then, members can obtain all the information necessary to be effective monitors.

C. Incentive

Like board members, members are volunteers, meaning they are subject to the same criticism. As Professor Kathleen Boozang puts it, “[M]embers, because they do not have a financial stake in the corporate enterprise, lack an incentive to monitor corporate behavior.” 79 Kathleen M. Boozang, Does an Independent Board Improve Nonprofit Corporate Governance?, 75 Tenn. L. Rev. 83, 125–26 (2007). However, members need not be financially disinterested in the nonprofit firm: They can be required to re-up their membership with periodic fees. Even without this mechanism, however, members provide a natural check on board authority.

While donors have no pecuniary self-interest in the charities they donate to, the act of giving money provides a built-in incentive to see that the money is spent well. 80 See Schizer, supra note 23, at 101 (“Wanting to get the most for their money, [donors] look for evidence that their gift is making a difference.”). Likewise, members can be made to care about the nonprofits they nominally oversee by requiring regular donations—in other words, dues. Statutes afford nonprofits wide latitude to demand consideration from members. For example, a District of Columbia statute based on the MNCA provides that “[a] membership corporation may levy dues, assessments, and fees on its members to the extent authorized in the articles of incorporation or bylaws.” 81 D.C. Code § 29-404.13 (2020). The statute continues, “Dues, assessments, and fees may be imposed on members of the same class either alike or in different amounts or proportions, and may be imposed on a different basis on different classes of members. Members of a class may be made exempt from dues, assessments, and fees . . . .” Id. Members may hesitate to pay regular dues if they have no intention of exercising the rights and powers of membership.

Even without consideration, however, membership provides a natural check on board members. In the analogous context of business corporations, the separation of powers among shareholders, boards, and management creates “a powerful set of checks and balances.” 82 Cynthia A. Montgomery & Rhonda Kaufman, The Board’s Missing Link, Harv. Bus. Rev. (Mar. 2003), https://hbr.org/2003/03/the-boards-missing-link (on file with the Columbia Law Review). Even if some or most members are disinterested in the business of corporate governance, even a handful of motivated members could, for example, call a special meeting, inspect the books, or attempt to remove a director. 83 See supra Part II. While members may not be optimally incentivized to govern, it does not follow that they will fail to add to the nonprofit governance equation. Rather, as with directors, it may be necessary to rely on members’ sense of duty and obligation to ensure they will engage in the business of nonprofit governance.

Conclusion

This Comment sheds light on the institution of membership and demonstrates how it can supply accountability to a sector that lacks it. Whereas the idea of a self-perpetuating board among business corporations is lambasted and rarely seen, it is the norm among nonprofits. Membership promises to fill this gap, supplying a principal that can be structured to meet the needs of the agent. The idea of membership for public charities is too novel at present for this Comment to go beyond merely suggesting that charities consider the idea. One can imagine a world, however, where the idea of membership in public-benefit nonprofits has been tried and tested and mandatory membership could be floated. After all, a principal without an agent is like a government without an electorate—that is to say, a dictatorship. Membership provides the promise of democracy.

Appendix

| Model Nonprofit Corporation Act (2008) | |

| Derivative action | Lesser of 5% or 50 members; § 13.02 |

| Books and records inspection | § 16.02 |

| Removal for cause | If elected by members; § 8.08 |

| Removal without cause | Default; § 8.08 |

| Special meeting | At least 10%, and no more than 25% of voting power; § 7.02 |

| Action by consents | Unanimous by default; § 7.04 |

| Vote on articles amendments required | If so entitled; § 10.03 |

| Power to propose amendment | 10% of members entitled to vote by default; § 10.03 |

| Alabama | |

| Derivative action | No; but see Ala. Code § 10A-3-2.44 (2020) |

| Books and records inspection | Ala. Code § 10A-3-2.32 |

| Removal for cause | According to articles; Ala. Code § 10A-3-2.09 |

| Removal without cause | According to articles; Ala. Code § 10A-3-2.09 |

| Special meeting | 5% by default; Ala. Code § 10A-3-2.02 |

| Action by consents | Unanimous; Ala. Code § 10A-3-2.14 |

| Vote on articles amendments required | 2/3 vote; Ala. Code § 10A-3-4.01 |

| Power to propose amendment | No |

| Alaska | |

| Derivative action | No; Angleton v. Cox, 238 P.3d 610, 617 (Alaska 2010) |

| Books and records inspection | Alaska Stat. § 10.20.131 (2020) |

| Removal for cause | No; Alaska Stat. § 10.20.126 |

| Removal without cause | No; Alaska Stat. § 10.20.126 |

| Special meeting | 5% by default; Alaska Stat. § 10.20.061 |

| Action by consents | Unanimous; Alaska Stat. § 10.20.695 |

| Vote on articles amendments required | 2/3 vote; Alaska Stat. § 10.20.176 |

| Power to propose amendment | No |

| Arizona | |

| Derivative action | Lesser of 25% or 50 members; Ariz. Rev. Stat. § 10-3631 (2020) |

| Books and records inspection | Ariz. Rev. Stat. § 10-11602 |

| Removal for cause | Default; Ariz. Rev. Stat. § 10-3808 |

| Removal without cause | Default; Ariz. Rev. Stat. § 10-3808 |

| Special meeting | 10% of members; Ariz. Rev. Stat. § 10-3702 |

| Action by consents | Majority by default; Ariz. Rev. Stat. § 10-3704 |

| Vote on articles amendments required | Lesser of 2/3 votes cast or majority of voting power; Ariz. Rev. Stat. § 10-11003 |

| Power to propose amendment | If provided by articles; Ariz. Rev. Stat. § 10-11003 |

| Arkansas | |

| Derivative action | Yes, with personal claim; Ark. Code Ann. § 4-28-609 (2020) |

| Books and records inspection | Ark. Code Ann. § 4-28-218 |

| Removal for cause | Yes; Ark. Code Ann. § 4-33-808 |

| Removal without cause | Yes; Ark. Code Ann. § 4-33-808 |

| Special meeting | If provided by governing documents; Ark. Code Ann. § 4-28-617 |

| Action by consents | Default; Ark. Code Ann. § 4-28-212 |

| Vote on articles amendments required | If provided by governing documents; Ark. Code Ann. § 4-28-212 |

| Power to propose amendment | No |

| California | |

| Derivative action | Yes, if suit “will benefit the corporation or its members”; Cal. Corp. Code § 5710 (2020) |

| Books and records inspection | Cal. Corp. Code § 6333 |

| Removal for cause | Yes; Cal. Corp. Code § 5222 |

| Removal without cause | Yes; Cal. Corp. Code § 5222 |

| Special meeting | 5%; Cal. Corp. Code § 5510 |

| Action by consents | Unanimous; Cal. Corp. Code § 5516 |

| Vote on articles amendments required | Yes; Cal. Corp. Code § 5812 |

| Power to propose amendment | Yes; Cal. Corp. Code § 5812 |

| Colorado | |

| Derivative action | 5%; Colo. Rev. Stat. § 7-126-401 (2020) |

| Books and records inspection | Explicitly provided for business corporations but not nonprofits; Colo. Rev. Stat. § 7-116-102 |

| Removal for cause | Yes; Colo. Rev. Stat. § 7-128-108 |

| Removal without cause | Default; Colo. Rev. Stat. § 7-128-108 |

| Special meeting | 10% by default; Colo. Rev. Stat. § 7-127-102 |

| Action by consents | Unanimous by default; Colo. Rev. Stat. § 7-127-107 |

| Vote on articles amendments required | Yes; Colo. Rev. Stat. § 7-130-103 |

| Power to propose amendment | 10% by default; Colo. Rev. Stat. § 7-130-103 |

| Connecticut | |

| Derivative action | Yes; Windesheim v. Hartland Pond Corp., No. LLICV136009344S, 2014 WL 5286573, at *1 (Conn. Super. Ct. Sept. 17, 2014) |

| Books and records inspection | Conn. Gen. Stat. § 33-1236 (2019) |

| Removal for cause | Yes; Conn. Gen. Stat. § 33-1088 |

| Removal without cause | Default; Conn. Gen. Stat. § 33-1088 |

| Special meeting | 5% by default; Conn. Gen. Stat. § 33-1062 |

| Action by consents | Unanimous; Conn. Gen. Stat. § 33-1064 |

| Vote on articles amendments required | 2/3 vote; Conn. Gen. Stat. § 33-1142 |

| Power to propose amendment | No |

| Delaware | |

| Derivative action | Yes; Del. Code tit. 8, § 327 (2020) |

| Books and records inspection | Del Code. tit. 8, § 220 |

| Removal for cause | Yes; Del. Code tit. 8, § 141 |

| Removal without cause | Default; Del. Code tit. 8, § 141 |

| Special meeting | If so provided; Del. Code tit. 8, §§ 211(d), 215(a) |

| Action by consents | Majority or otherwise; Del. Code tit. 8, § 228 |

| Vote on articles amendments required | Yes; Del. Code tit. 8, § 242 |

| Power to propose amendment | No |

| District of Columbia | |

| Derivative action | Lesser of 5% or 50; D.C. Code § 29-411.02 (2020) |

| Books and records inspection | D.C. Code § 29-413.02 |

| Removal for cause | Yes; D.C. Code § 29-406.08 |

| Removal without cause | Default; D.C. Code § 29-406.08 |

| Special meeting | No more than 25% of members; D.C. Code § 29-405.02 |

| Action by consents | Yes; D.C. Code § 29-405.04 |

| Vote on articles amendments required | Yes; D.C. Code § 29-408.03 |

| Power to propose amendment | 10% default; D.C. Code § 29-408.03 |

| Florida | |

| Derivative action | Yes; Fla. Stat. § 617.07401 (2019) |

| Books and records inspection | Fla. Stat. § 617.1602 |

| Removal for cause | If elected by members; Fla. Stat. § 617.0808 |

| Removal without cause | If elected by members; Fla. Stat. § 617.0808 |

| Special meeting | 5%; Fla. Stat. § 617.0701 |

| Action by consents | Default; Fla. Stat. § 617.0701 |

| Vote on articles amendments required | If so entitled; Fla. Stat. § 617.1002 |

| Power to propose amendment | No |

| Georgia | |

| Derivative action | Lesser of 5% or 50 members; Ga. Code Ann. § 14-3-741 (2019) |

| Books and records inspection | Ga. Code Ann. § 14-3-1602 |

| Removal for cause | Default; Ga. Code Ann. § 14-3-808 |

| Removal without cause | Default; Ga. Code Ann. § 14-3-808 |

| Special meeting | 5% by default; Ga. Code Ann. § 14-3-702 |

| Action by consents | Yes; Ga. Code Ann. § 14-3-704 |

| Vote on articles amendments required | 2/3 by default; Ga. Code Ann. § 14-3-1003 |

| Power to propose amendment | No |

| Hawaii | |

| Derivative action | Lesser of 5% or 50 members; Haw. Rev. Stat. § 414D-90 (2020) |

| Books and records inspection | Haw. Rev. Stat. § 414D-104 |

| Removal for cause | Default; Haw. Rev. Stat. § 414D-138 |

| Removal without cause | Default; Haw. Rev. Stat. § 414D-138 |

| Special meeting | 5% by default; Haw. Rev. Stat. § 414D-102 |

| Action by consents | 80% unless limited or prohibited; Haw. Rev. Stat. § 414D-104 |

| Vote on articles amendments required | 2/3 by default; Haw. Rev. Stat. § 414D-182 |

| Power to propose amendment | No |

| Idaho | |

| Derivative action | Lesser of 5% or 50 members; Idaho Code § 30-411 (2020) |

| Books and records inspection | Idaho Code § 30-1102 |

| Removal for cause | If elected by members; Idaho Code § 30-608 |

| Removal without cause | If elected by members; Idaho Code § 30-608 |

| Special meeting | 10%; Idaho Code § 30-502 |

| Action by consents | 80% unless limited or prohibited; Idaho Code § 30-504 |

| Vote on articles amendments required | Lesser of 2/3 votes or majority of voting power; Idaho Code § 30-703 |

| Power to propose amendment | No |

| Illinois | |

| Derivative action | Yes; 805 Ill. Comp. Stat. Ann. 105/107.80 (West 2020) |

| Books and records inspection | 805 Ill. Comp. Stat. Ann. 105/107.75 |

| Removal for cause | 2/3 vote; 805 Ill. Comp. Stat. Ann. 105/108.35 |

| Removal without cause | 2/3 vote; 805 Ill. Comp. Stat. Ann. 105/108.35 |

| Special meeting | 5% by default; 805 Ill. Comp. Stat. Ann. 105/107.05 |

| Action by consents | Majority by default; 805 Ill. Comp. Stat. Ann. 105/107.10 |

| Vote on articles amendments required | 2/3 if so entitled, by default; 805 Ill. Comp. Stat. Ann. 105/110.20 |

| Power to propose amendment | No |

| Indiana | |

| Derivative action | Yes; Kirtley v. McClelland, 562 N.E.2d 27, 31 (Ind. Ct. App. 1990) |

| Books and records inspection | Ind. Code § 23-17-27-2 (2020) |

| Removal for cause | Unless otherwise provided by articles; Ind. Code § 23-17-12-8 |

| Removal without cause | Unless otherwise provided by articles; Ind. Code § 23-17-12-8 |

| Special meeting | 10%; Ind. Code § 23-17-10-2 |

| Action by consents | 80% unless limited or prohibited; Ind. Code § 23-17-10-4 |

| Vote on articles amendments required | Yes; Ind. Code § 23-17-17-5 |

| Power to propose amendment | No |

| Iowa | |

| Derivative action | Lesser of 5% or 50 members; Iowa Code § 504.632 (2020) |

| Books and records inspection | Iowa Code § 504.1602 |

| Removal for cause | Default; Iowa Code § 504.808 |

| Removal without cause | Default; Iowa Code § 504.808 |

| Special meeting | 5% of voting power by default; Iowa Code § 504.702 |

| Action by consents | 80% unless limited or prohibited; Iowa Code § 504.704 |

| Vote on articles amendments required | Lesser of 2/3 votes or majority of voting power; Iowa Code § 504.1003 |

| Power to propose amendment | No |

| Kansas | |

| Derivative action | Yes; Kan. Stat. Ann. § 60-223a (West 2020) |

| Books and records inspection | Kan. Stat. Ann. § 17-6510 |

| Removal for cause | Yes; Kan. Stat. Ann. § 17-6301 |

| Removal without cause | Yes; Kan. Stat. Ann. § 17-6301 |

| Special meeting | If provided by governing documents; Kan. Stat. Ann. § 17-6501 |

| Action by consents | Unless otherwise provided by articles; Kan. Stat. Ann. § 17-6518 |

| Vote on articles amendments required | If provided by articles; Kan. Stat. Ann. § 17-6602 |

| Power to propose amendment | No |

| Kentucky | |

| Derivative action | No; Porter v. Shelbyville Cemetery Co., No. 2007-CA-002545-MR, 2009 WL 722995, at *5 (Ky. Ct. App. Mar. 20, 2009) |

| Books and records inspection | Default; Ky. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 273.233 (West 2020) |

| Removal for cause | If so provided; Ky. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 273.211 |

| Removal without cause | If so provided; Ky. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 273.211 |

| Special meeting | 5% by default; Ky. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 273.193 |

| Action by consents | Unanimous; Ky. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 273.377 |

| Vote on articles amendments required | At least 2/3 if so entitled; Ky. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 273.263 |

| Power to propose amendment | No |

| Louisiana | |

| Derivative action | Yes; see Mary v. Lupin Found., 609 So. 2d 184, 185–86 (La. 1992) |

| Books and records inspection | La. Stat. Ann. § 12:223 (2020) |

| Removal for cause | Yes; La. Stat. Ann. § 12:224 |

| Removal without cause | Yes; La. Stat. Ann. § 12:224 |

| Special meeting | If so provided; La. Stat. Ann. § 12:229 |

| Action by consents | Unanimous; La. Stat. Ann. § 12:233 |

| Vote on articles amendments required | 2/3 by default; La. Stat. Ann. § 12:237 |

| Power to propose amendment | If so provided; La. Stat. Ann. § 12:237 |

| Maine | |

| Derivative action | No; America v. Sunspray Condo. Ass’n, 61 A.3d 1249, 1254–55 (Me. 2013) |

| Books and records inspection | If entitled to vote; Me. Rev. Stat. Ann. tit. 13-B, § 715 (2020) |

| Removal for cause | If elected by members; Me. Rev. Stat. Ann. tit. 13-B, § 704 |

| Removal without cause | If elected by members; Me. Rev. Stat. Ann. tit. 13-B, § 704 |

| Special meeting | 5% by default; Me. Rev. Stat. Ann. tit. 13-B, § 602 |

| Action by consents | Unanimous; Me. Rev. Stat. Ann. tit. 13-B, § 606 |

| Vote on articles amendments required | Majority by default; Me. Rev. Stat. Ann. tit. 13-B, § 802 |

| Power to propose amendment | No |

| Maryland | |

| Derivative action | Yes; First Baptist Church of Friendly v. Beeson, 841 A.2d 347, 354 n.13 (Md. Ct. Spec. App. 2004) |

| Books and records inspection | 5% of any class; Md. Code Ann., Corps. & Ass’ns § 2-513 (West 2020) |

| Removal for cause | Default; Md. Code Ann., Corps. & Ass’ns § 2-406 |

| Removal without cause | Default; Md. Code Ann., Corps. & Ass’ns § 2-406 |

| Special meeting | If so provided; Md. Code Ann., Corps. & Ass’ns § 2-502 |

| Action by consents | Unanimous; Md. Code Ann., Corps. & Ass’ns § 2-505 |

| Vote on articles amendments required | 2/3 if so entitled; Md. Code Ann., Corps. & Ass’ns § 2-604 |

| Power to propose amendment | No |

| Massachusetts | |

| Derivative action | Yes; Mass. R. Civ. P. 23.2 |

| Books and records inspection | Mass. Gen. Laws Ann. ch. 180, § 18 (West 2020) |

| Removal for cause | If so provided; Mass. Gen. Laws Ann. ch. 180, § 6A |

| Removal without cause | If so provided; Mass. Gen. Laws Ann. ch. 180, § 6A |

| Special meeting | 10% of smallest quorum entitled to vote; Mass. Gen. Laws Ann. ch. 180, § 6A |

| Action by consents | Unclear; but see Mass. Gen. Laws. Ann. ch. 156B, § 43 (providing for unanimous consent in business corporations) |

| Vote on articles amendments required | 2/3 if so entitled; Mass. Gen. Laws Ann. ch. 180, § 7 |

| Power to propose amendment | If so provided; Mass. Gen. Laws Ann. ch. 180, § 7 |

| Michigan | |

| Derivative action | Yes; Mich. Comp. Laws Ann. § 450.2492a (West 2020) |

| Books and records inspection | Mich. Comp. Laws Ann. § 450.2487 |

| Removal for cause | Yes; Mich. Comp. Laws Ann. § 450.2511 |

| Removal without cause | Unless otherwise provided by articles; Mich. Comp. Laws Ann. § 450.2511 |

| Special meeting | 10%; Mich. Comp. Laws Ann. § 450.2403 |

| Action by consents | Unanimous unless lower threshold provided in articles; Mich. Comp. Laws Ann. § 450.2407 |

| Vote on articles amendments required | Yes; Mich. Comp. Laws Ann. § 450.2611 |

| Power to propose amendment | Yes; Mich. Comp. Laws Ann. § 450.2611 |

| Minnesota | |

| Derivative action | Yes; Cf. Janssen v. Best & Flanagan, 662 N.W.2d 876, 886–87 (Minn. 2003) |

| Books and records inspection | Minn. Stat. § 317A.461 (2019) |

| Removal for cause | Default, if elected by members; Minn. Stat. § 317A.341 |

| Removal without cause | Default, if elected by members; Minn. Stat. § 317A.341 |

| Special meeting | Lesser of 10% or 50 members; Minn. Stat. § 317A.433 |

| Action by consents | Unanimous; Minn. Stat. § 317A.445 |

| Vote on articles amendments required | Yes; Minn. Stat. § 317A.133 |

| Power to propose amendment | Yes; Minn. Stat. § 317A.133 |

| Mississippi | |

| Derivative action | Lesser of 5% or 50 members; Miss. Code Ann. § 79-11-193 (2020) |

| Books and records inspection | Miss. Code Ann. § 79-11-285 |

| Removal for cause | Yes; Miss. Code Ann. § 79-11-245 |

| Removal without cause | Yes; Miss. Code Ann. § 79-11-245 |

| Special meeting | 5%; Miss. Code Ann. § 79-11-199 |

| Action by consents | 80% unless limited or prohibited; Miss. Code Ann. § 79-11-203 |

| Vote on articles amendments required | Lesser of 2/3 votes or majority of voting power; Miss. Code Ann. § 79-11-301 |

| Power to propose amendment | No; Miss. Code Ann. § 79-11-301 |

| Missouri | |

| Derivative action | Lesser of 10% or 50 members; Mo. Ann. Stat. § 355.221 (West 2020) |

| Books and records inspection | Mo. Ann. Stat. § 355.826 |

| Removal for cause | If elected by members; Mo. Ann. Stat. § 355.346 |

| Removal without cause | If elected by members; Mo. Ann. Stat. § 355.346 |

| Special meeting | 5%; Mo. Ann. Stat. § 355.236 |

| Action by consents | 80% unless limited or prohibited; Mo. Ann. Stat. § 255.246 |

| Vote on articles amendments required | Lesser of 2/3 votes or majority voting power; Mo. Ann. Stat. § 355.561 |

| Power to propose amendment | No |

| Montana | |

| Derivative action | Lesser of 5% or 50 members; Mont. Code Ann. § 35-2-1301 (West 2019) |

| Books and records inspection | Mont. Code Ann. § 35-2-907 |

| Removal for cause | If elected by members; Mont. Code Ann. § 35-2-421 |

| Removal without cause | If elected by members; Mont. Code Ann. § 35-2-421 |

| Special meeting | 5%; Mont. Code Ann. § 35-2-527 |

| Action by consents | 80% unless limited or prohibited; Mont. Code Ann. § 35-2-529 |

| Vote on articles amendments required | Lesser of 2/3 votes or majority of voting power; Mont. Code Ann. § 35-2-223 |

| Power to propose amendment | Yes; Mont. Code Ann. § 35-2-223 |

| Nebraska | |

| Derivative action | Lesser of 5% or 50 members; Neb. Rev. Stat. § 21-1949 (2020) |

| Books and records inspection | Neb. Rev. Stat. § 21-19,166 |

| Removal for cause | If elected by members; Neb. Rev. Stat. § 21-1975 |

| Removal without cause | If elected by members; Neb. Rev. Stat. § 21-1975 |

| Special meeting | 5% of voting power; Neb. Rev. Stat. § 21-1952 |

| Action by consents | 80% unless limited or prohibited; Neb. Rev. Stat. § 21-1954 |

| Vote on articles amendments required | If so provided by bylaws; Neb. Rev. Stat. § 21-19,107 |

| Power to propose amendment | Yes; Neb. Rev. Stat. § 21-19,107 |

| Nevada | |

| Derivative action | Yes; Nev. R. Civ. P. § 23.1 |

| Books and records inspection | 15% of members; Nev. Rev. Stat. § 82.186 (2019) |

| Removal for cause | If elected by members; Nev. Rev. Stat. § 82.296 |

| Removal without cause | If elected by members; Nev. Rev. Stat. § 82.296 |

| Special meeting | 5% of members; Nev. Rev. Stat. § 82.336 |

| Action by consents | Default; Nev. Rev. Stat. § 82.276 |

| Vote on articles amendments required | If so entitled; Nev. Rev. Stat. 82.356 |

| Power to propose amendment | No; Nev. Rev. Stat. § 82.356 |

| New Hampshire | |

| Derivative action | Unclear; but see N.H. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 293-A:7.41 (2020) (providing action to shareholders of business corporations) |

| Books and records inspection | If so provided in bylaws; N.H. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 292:6 |

| Removal for cause | If so provided in bylaws; N.H. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 292:6 |

| Removal without cause | If so provided in bylaws; N.H. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 292:6 |

| Special meeting | If so provided in bylaws; N.H. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 292:6 |

| Action by consents | If so provided in bylaws; N.H. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 292:6 |

| Vote on articles amendments required | No; N.H. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 292:7 |

| Power to propose amendment | If so provided; N.H. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 292:7 |

| New Jersey | |

| Derivative action | Yes; see, e.g., Valle v. N. Jersey Auto. Club, 376 A.2d 1192, 1193 (N.J. 1977) |

| Books and records inspection | No, but see N.J. Stat. Ann. § 15A:5-24 (West 2020) (providing access to specified documents) |

| Removal for cause | If elected by members; N.J. Stat. Ann. § 15A:6-6 |

| Removal without cause | If elected by members; N.J. Stat. Ann. § 15A:6-6 |

| Special meeting | 10% of those entitled to vote; N.J. Stat. Ann. § 15A:5-3 |

| Action by consents | Default; N.J. Stat. Ann. § 15A:5-6 |

| Vote on articles amendments required | 2/3 votes of members so entitled; N.J. Stat. Ann. § 15A:9-2 |

| Power to propose amendment | No; N.J. Stat. Ann. § 15A:9-2 |

| New Mexico | |

| Derivative action | Unclear; see Saylor v. Valles, 63 P.3d 1152, 1156 (N.M. Ct. App. 2002) (declining to reach the standing question) |

| Books and records inspection | N.M. Stat. Ann. § 53-8-27 (West 2020) |

| Removal for cause | If so provided; N.M. Stat. Ann. § 53-8-18 |

| Removal without cause | If so provided; N.M. Stat. Ann. § 53-8-18 |

| Special meeting | 5% of voting power by default; N.M. Stat. Ann. § 53-8-13 |

| Action by consents | Unanimous; N.M. Stat. Ann. § 53-8-97 |

| Vote on articles amendments required | 2/3 votes of members so entitled; N.M. Stat. Ann. § 53-8-36 |

| Power to propose amendment | No; N.M. Stat. Ann. § 53-8-36 |

| New York | |

| Derivative action | 5% of votes or members of any class; N.Y. Not-for-Profit Corp. Law § 623 (McKinney 2020) |

| Books and records inspection | N.Y. Not-for-Profit Corp. Law § 621 |

| Removal for cause | Yes; N.Y. Not-for-Profit Corp. Law § 706 |

| Removal without cause | Yes; N.Y. Not-for-Profit Corp. Law § 706 |

| Special meeting | 10%; N.Y. Not-for-Profit Corp. Law § 603 |

| Action by consents | Unanimous; N.Y. Not-for-Profit Corp. Law § 614 |

| Vote on articles amendments required | If so entitled; N.Y. Not-for-Profit Corp. Law § 802 |

| Power to propose amendment | Yes; N.Y. Not-for-Profit Corp. Law § 802 |

| North Carolina | |

| Derivative action | Yes; N.C. Gen. Stat. § 55A-7-40 (2020) |

| Books and records inspection | N.C. Gen. Stat § 55A-16-02 |

| Removal for cause | If elected by members; N.C. Gen. Stat. § 55A-8-08 |

| Removal without cause | If elected by members, by default; N.C. Gen. Stat. § 55A-8-08 |

| Special meeting | 10%; N.C. Gen. Stat. § 55A-7-02 |

| Action by consents | Unanimous; N.C. Gen. Stat. § 55A-7-04 |

| Vote on articles amendments required | Lesser of 2/3 votes of those so entitled or majority of voting power; N.C. Gen. Stat. § 55A-10-03 |

| Power to propose amendment | Yes; N.C. Gen. Stat. § 55A-10-03 |

| North Dakota | |

| Derivative action | Lesser of 10% or 50 members with voting rights; N.D. Cent. Code § 10-33-81 (2019) |

| Books and records inspection | N.D. Cent. Code § 10-33-80 |

| Removal for cause | If eligible to vote, by default; N.D. Cent. Code § 10-33-36 |

| Removal without cause | If eligible to vote, by default; N.D. Cent. Code § 10-33-36 |

| Special meeting | Lesser of 10% or 50 members with voting rights; N.D. Cent. Code § 10-33-66 |

| Action by consents | Unanimous unless lower threshold provided; N.D. Cent. Code § 10-33-73 |

| Vote on articles amendments required | If members have voting rights; N.D. Cent. Code § 10-33-15 |

| Power to propose amendment | Yes; N.D. Cent. Code § 10-33-15 |

| Ohio | |

| Derivative action | Yes; see Miller v. Bargaheiser, 591 N.E.2d 1339, 1343 (Ohio Ct. App. 1990) |

| Books and records inspection | Subject to limitations in governing documents; Ohio Rev. Code Ann. § 1702.15 (2020) |

| Removal for cause | If so provided; Ohio Rev. Code Ann. § 1702.29 |

| Removal without cause | If so provided; Ohio Rev. Code Ann. § 1702.29 |

| Special meeting | Lesser of 10% or 25 members, unless governing documents call for majority; Ohio Rev. Code Ann. § 1702.17 |

| Action by consents | Unanimous unless prohibited by bylaws; Ohio Rev. Code Ann. § 1702.25 |

| Vote on articles amendments required | Yes, subject to threshold set in governing documents; Ohio Rev. Code Ann. § 1702.38 |

| Power to propose amendment | Yes; Ohio Rev. Code Ann. § 1702.38 |

| Oklahoma | |

| Derivative action | Okla. Stat. tit. 18, § 1126 (2020) |

| Books and records inspection | Okla. Stat. tit. 18, § 1065 |

| Removal for cause | Yes; Okla. Stat. tit. 18, § 1027 |

| Removal without cause | Yes; Okla. Stat. tit. 18, § 1027 |

| Special meeting | If so provided; Okla. Stat. tit. 18, § 1056 |

| Action by consents | Unless otherwise provided by articles; Okla. Stat. tit. 18, § 1073 |

| Vote on articles amendments required | Yes; Okla. Stat. tit. 18, § 1077 |

| Power to propose amendment | No; Okla. Stat. tit. 18, § 1077 |

| Oregon | |

| Derivative action | Lesser of 2% or 20 members; Or. Rev. Stat. § 65.174 (2019) |

| Books and records inspection | Or. Rev. Stat. § 65.774 |

| Removal for cause | Default; Or. Rev. Stat. § 65.324 |

| Removal without cause | Default; Or. Rev. Stat. § 65.324 |

| Special meeting | 5%; Or. Rev. Stat. § 65.204 |

| Action by consents | Unanimous, unless prohibited; Or. Rev. Stat. § 65.211 |

| Vote on articles amendments required | Lesser of 2/3 votes of those so entitled or majority of voting power; Or. Rev. Stat. § 65.437 |

| Power to propose amendment | Yes; Or. Rev. Stat. § 65.437 |

| Pennsylvania | |

| Derivative action | Yes; 15 Pa. Cons. Stat. § 5781 (2020) |

| Books and records inspection | 15 Pa. Cons. Stat. § 5508 |

| Removal for cause | Unless otherwise provided in bylaw adopted by members; 15 Pa. Cons. Stat. § 5726 |

| Removal without cause | Unless otherwise provided in bylaw adopted by members; 15 Pa. Cons. Stat. § 5726 |

| Special meeting | 10%; 15 Pa. Cons. Stat. § 5755 |

| Action by consents | Unanimous unless restricted by bylaws; 15 Pa. Cons. Stat. § 5766 |

| Vote on articles amendments required | If so entitled; 15 Pa. Cons. Stat. § 5912 |

| Power to propose amendment | 10% by default; 15 Pa. Cons. Stat. § 5912 |

| Rhode Island | |

| Derivative action | Yes; R.I. Super. Ct. R. Civ. P. 23.1 |

| Books and records inspection | 7 R.I. Gen. Laws § 7-6-30 (2020) |

| Removal for cause | If so provided; 7 R.I. Gen. Laws § 7-6-23 |

| Removal without cause | If so provided; 7 R.I. Gen. Laws § 7-6-23 |

| Special meeting | If so provided; 7 R.I. Gen. Laws § 706-18 |

| Action by consents | Unanimous; 7 R.I. Gen. Laws § 7-6-104 |

| Vote on articles amendments required | If so entitled; 7 R.I. Gen. Laws § 7-6-39 |

| Power to propose amendment | No; 7 R.I. Gen. Laws § 7-6-39 |

| South Carolina | |

| Derivative action | Yes; S.C. Code Ann. § 33-31-630 (2020) |

| Books and records inspection | S.C. Code Ann. § 33-31-1602 |

| Removal for cause | If elected by members; S.C. Code Ann. § 33-31-808 |

| Removal without cause | If elected by members; S.C. Code Ann. § 33-31-808 |

| Special meeting | 5%; S.C. Code Ann. § 33-31-702 |

| Action by consents | 80% unless limited or prohibited; S.C. Code Ann. § 33-31-704 |

| Vote on articles amendments required | Lesser of 2/3 votes of those so entitled or majority of voting power; S.C. Code Ann. § 33-31-1003 |

| Power to propose amendment | Yes; S.C. Code Ann. § 33-31-1003 |

| South Dakota | |

| Derivative action | Unclear; but see S.D. Codified Laws § 47-1A-741 (2020) (providing action to shareholders of business corporations) |

| Books and records inspection | S.D. Codified Laws § 47-24-2 (2020) |

| Removal for cause | If so provided; S.D. Codified Laws § 47-23-18 |

| Removal without cause | If so provided; S.D. Codified Laws § 47-23-18 |

| Special meeting | 5% by default; S.D. Codified Laws § 47-23-5 |

| Action by consents | Unanimous; S.D. Codified Laws § 47-23-6 |

| Vote on articles amendments required | If so entitled; S.D. Codified Laws § 47-22-16 |

| Power to propose amendment | If entitled to vote thereon; S.D. Codified Laws § 47-22-16 |

| Tennessee | |

| Derivative action | Lesser of 5% or 50 members; Tenn. Code Ann. § 48-56-401 (2020) |

| Books and records inspection | Tenn. Code Ann. § 48-66-102 |

| Removal for cause | If elected by members; Tenn. Code Ann. § 48-58-108 |

| Removal without cause | If elected by members, by default; Tenn. Code Ann. § 48-58-108 |

| Special meeting | 10% default; Tenn. Code Ann. § 48-57-102 |

| Action by consents | Unanimous unless lesser threshold provided; Tenn. Code Ann. § 48-57-104 |

| Vote on articles amendments required | Lesser of 2/3 votes or majority of voting power; Tenn. Code Ann. § 48-60-103 |

| Power to propose amendment | Yes; Tenn. Code Ann. § 48-60-103 |

| Texas | |

| Derivative action | No; Tran v. Hoang, 481 S.W.3d 313, 317 (Tex. App. 2015) |

| Books and records inspection | Tex. Bus. Orgs. Code § 22.353 (2019) |

| Removal for cause | Default; Tex. Bus. Orgs Code § 22.211 |

| Removal without cause | Default; Tex. Bus. Orgs. Code § 22.211 |

| Special meeting | 10%; Tex. Bus. Orgs. Code § 22.155 |

| Action by consents | No; Cf. Tex. Bus. Orgs. Code § 22.220 (providing for director consents, but explicitly excluding members) |

| Vote on articles amendments required | 2/3; Tex. Bus. Orgs. Code §§ 22.105, 22.164 |

| Power to propose amendment | No; Tex. Bus. Orgs. Code § 22.101 |

| Utah | |

| Derivative action | Voting members; Utah Code § 16-6a-612 (2020) |

| Books and records inspection | Utah Code § 16-6a-1602 |

| Removal for cause | If elected by members; Utah Code § 16-6a-808 |

| Removal without cause | If elected by members, and unless otherwise provided in bylaws; Utah Code § 16-6a-808 |

| Special meeting | 10% by default; Utah Code § 16-6a-702 |

| Action by consents | Unless otherwise provided by articles; Utah Code 16-6a-707 |

| Vote on articles amendments required | If so entitled; Utah Code § 16-6a-1003 |

| Power to propose amendment | 10% by default if entitled to vote thereon; Utah Code § 16-6a-1003 |

| Vermont | |

| Derivative action | Lesser of 5% or 50 members; Vt. Stat. Ann. tit. 11B, § 6.40 (2020) |

| Books and records inspection | Vt. Stat. Ann. tit. 11B, § 16.02 |

| Removal for cause | If elected by members; Vt. Stat. Ann. tit. 11B, § 8.08 |

| Removal without cause | If elected by members; Vt. Stat. Ann. tit. 11B, § 8.08 |

| Special meeting | 5%; Vt. Stat. Ann. tit. 11B, § 7.02 |

| Action by consents | Unanimous by default; Vt. Stat. Ann. tit. 11B, § 7.04 |

| Vote on articles amendments required | Lesser of 2/3 votes or majority of voting power; Vt. Stat. Ann. tit. 11B, § 10.03 |

| Power to propose amendment | Yes; Vt. Stat. Ann. tit. 11B, § 10.03 |

| Virginia | |

| Derivative action | For willful misconduct or ultra vires; Richelieu v. Kirby, No. 157001, 1999 WL 262444 at *2 (Va. Cir. Ct. Mar. 5, 1999) |

| Books and records inspection | Va. Code § 13.1-933 (2020) |

| Removal for cause | Yes; Va. Code § 13.1-860 |

| Removal without cause | Unless otherwise provided in articles; Va. Code § 13.1-860 |

| Special meeting | 5% by default; Va. Code § 13.1-839 |

| Action by consents | Unanimous unless otherwise provided by articles; Va. Code § 13.1-841 |

| Vote on articles amendments required | 2/3 unless a lower threshold is provided by articles; Va. Code § 13.1-886 |

| Power to propose amendment | No; Va. Code § 13.1-886 |

| Washington | |

| Derivative action | Yes; see, e.g., Davis v. Cox, 351 P.3d 862, 866 (Wash. 2015) |

| Books and records inspection | Wash Rev. Code § 24.03.135 (2020) |

| Removal for cause | 2/3 by default, if elected by members; Wash. Rev. Code § 24.03.103 |

| Removal without cause | 2/3 by default, if elected by members; Wash. Rev. Code § 24.03.103 |

| Special meeting | 5% by default; Wash. Rev. Code § 24.03.075 |

| Action by consents | Unanimous; Wash. Rev. Code § 24.03.465 |

| Vote on articles amendments required | 2/3 if so entitled; Wash. Rev. Code § 24.03.165 |

| Power to propose amendment | No; Wash. Rev. Code § 24.03.165 |

| West Virginia | |

| Derivative action | No; John A. Sheppard Mem’l Ecological Rsrv., Inc. v. Fanning, 836 S.E.2d 426, 431 (W. Va. 2019) |

| Books and records inspection | W. Va. Code Ann. § 31E-15-1502 (LexisNexis 2020) |

| Removal for cause | If entitled to vote; W. Va. Code Ann. § 31E-8-809 |

| Removal without cause | If entitled to vote, by default; W. Va. Code Ann. § 31E-8-809 |

| Special meeting | 5% or other percentage as provided; W. Va. Code Ann. § 31E-7-702 |

| Action by consents | Unanimous; W. Va. Code Ann. § 31E-7-704 |

| Vote on articles amendments required | 2/3 if so entitled; W. Va. Code Ann. § 31E-10-1003 |

| Power to propose amendment | No; W. Va. Code Ann. § 31E-10-1003 |

| Wisconsin | |

| Derivative action | Lesser of 5% or 50 members; Wis. Stat. § 181.0741 (2020) |

| Books and records inspection | Wis. Stat. § 181.1602 |

| Removal for cause | If elected by members; Wis. Stat. § 181.0808 |

| Removal without cause | If elected by members; Wis. Stat. § 181.0808 |

| Special meeting | 5% or other percentage as provided; Wis. Stat. § 181.0702 |

| Action by consents | 80% by default; Wis. Stat. § 181.0704 |

| Vote on articles amendments required | Lesser of 2/3 votes or majority of voting power; Wis. Stat. § 181.1003 |

| Power to propose amendment | Yes; Wis. Stat. § 181.1003 |

| Wyoming | |

| Derivative action | Lesser of 5% or 50 members; Wyo. Stat. Ann. § 17-19-630 (2020) |

| Books and records inspection | Wyo. Stat. Ann. § 17-19-1602 |

| Removal for cause | If elected by members; Wyo. Stat. Ann. § 17-19-808 |

| Removal without cause | If elected by members; Wyo. Stat. Ann. § 17-19-808 |

| Special meeting | 5%; Wyo. Stat. Ann. § 17-19-702 |

| Action by consents | 90% unless limited or prohibited; Wyo. Stat. Ann. § 17-19-704 |

| Vote on articles amendments required | Lesser of 2/3 votes or majority of voting power; Wyo. Stat. Ann. § 17-19-1003 |

| Power to propose amendment | Yes; Wyo. Stat. Ann. § 17-19-1003 |