The most elite and scarce of all U.S. legal credentials is serving as a Justice on the U.S. Supreme Court. A close second is clerking for a Justice. A Court clerkship is a prize as well as a ticket to future success. Rich accounts of the experience fill bookshelves and journal pages. Yet the public lacks a clear story about who wins this clerkship lottery. Original analysis of forty years of clerkships tells that story. New datasets detail clerks’ paths from college to the Court to careers. Research shows that Court clerkships favor educational pedigree and status over pure achievement. Post-Court, clerks enjoy a bounty of opportunities that amplify their influence on society writ large. In the elite legal labor market, some people are, in fact, more equal than others. 1

Introduction

The most valuable credential any young lawyer can earn is a clerkship on the United States Supreme Court.

2

Artemus Ward and David Weiden start their historical study by stating:

“Clerking for a U.S. Supreme Court justice is the most prestigious position a recent law school graduate can attain. . . . Supreme Court law clerks, past and present, are at the top of the legal profession. Law clerks are part of the legal, political, and business elite.” Artemus Ward & David L. Weiden, Sorcerers’ Apprentices: 100 Years of Law Clerks at the United States Supreme Court 1 (2006). Chambers Associate, a guide to law firms and legal employment, says on its website: “Clerking at the Supreme Court of the United States is the holy grail, the most prestigious gig any law grad can get.” SCOTUS Clerkships, Chambers Assoc., https://www.chambers-associate.com/where-to-start/getting-hired/scotus-clerkships [https://perma.cc/3N9J-WCRY] (last visited Aug. 9, 2023).

A Supreme Court clerkship affords the opportunity to train directly under one of the nine sitting Supreme Court Justices, helping make the nation’s most consequential decisions.

3

See, e.g., William H. Rehnquist, Opinion, Who Writes Decisions of the Supreme Court?, U.S. News & World Rep., Dec. 13, 1957, at 74, 74 (Dec. 9, 2008), [hereinafter Rehnquist, Who Writes Decisions] (describing, as a recent former Court clerk, how clerks influence Justices’ votes); see also Chad Oldfather & Todd C. Peppers, Judicial Assistants or Junior Judges: The Hiring, Utilization, and Influence of Law Clerks, 98 Marq. L. Rev. 1, 2–3 (2014) (“While Rehnquist backtracked in the face of public challenges raised by other former law clerks . . . he had opened the door for subsequent critiques [of clerks’ influence].”).

Many legal employers, from the fanciest law firms to elite government institutions and law schools, fall over themselves to hire former Supreme Court clerks, promising them fast tracks to equity partnerships, chaired professorships, and so on.

4

See Joan Biskupic, Clerks Gain Status, Clout in the ‘Temple’ of Justice, Wash. Post (Jan. 2, 1994), https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1994/01/02/clerks-gain-status-clout-in-the-temple-of-justice/31e5bba4-7064-4634-b8a5-b8a83615195d/ (on file with the Columbia Law Review) (“When they leave the marbled halls of the Supreme Court, they are guaranteed near-reverence in Washington’s world of lawyers, a fat salary and a chance for power and influence in a town where credentials sell.”); Tony Mauro & Vanessa Blum, SCOTUS Clerks: The Story Behind the Story, Yahoo! News (Dec. 11, 2017), https://www.yahoo.com/news/scotus-law-clerks-story-behind-114246460.html [https://perma.cc/29JE-UND5] (describing the hiring bonuses and numerous career opportunities available to former Supreme Court clerks).

Top law firms are willing to pay signing bonuses of almost half a million dollars.

5

See Bruce Love, Signing Bonuses for Supreme Court Clerks Are Set for Another Jump, Nat’l L.J. (July 14, 2021), https://www.law.com/nationallawjournal/2021/07/14/signing-bonuses-for-supreme-court-clerks-are-set-for-another-jump/ (on file with the Columbia Law Review) (reporting that some law firms were increasing their signing bonuses for Supreme Court clerks to $450,000).

Conventional wisdom is that the clerkship assures life success.

6

See William E. Nelson, Harvey Rishikof, I. Scott Messinger & Michael Jo, The Liberal Tradition of the Supreme Court Clerkship: Its Rise, Fall, and Reincarnation?, 62 Vand. L. Rev. 1749, 1753 (2009) [hereinafter Nelson et al., The Liberal Tradition] (offering the first empirical study of post-clerkship employment).

Typically, there are no more than thirty-six clerk slots 7 Retired Justices are allowed to hire a clerk, which modestly adds to the total, depending on the year. See, e.g., Rory K. Little, Clerking for a Retired Supreme Court Justice—My Experience of Being “Shared” Among Five Justices in One Term, 88 Geo. Wash. L. Rev. Arguendo 83, 85–86 (2020), https://www.gwlr.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/88-Geo.-Wash.-L.-Rev.-Arguendo-83.pdf [https://perma.cc/KF9K-3STN] (detailing the author’s experience as a clerk for a retired Justice). on the Court—or one slot for every one thousand law school graduates. 8 For annual statistics on ABA-approved law schools, see Various Statistics on ABA Law Schools, ABA, https://www.americanbar.org/groups/legal_education/resources/statistics/ [https://perma.cc/V9WL-AZQK] (last visited Aug. 9, 2023) (reporting the results of 509 Required Disclosures and other reports provided annually by all ABA-approved law schools). Candidates tick all the boxes: selective law school, top grades, law review membership, and glowing references from law faculty. 9 Newspapers and legal periodicals episodically profile Supreme Court clerks. See, e.g., Rex Bossert, Clerks’ Route to Top Court; Their Choice of Circuit and Judge Shapes Chance to Serve Supremes, Nat’l L.J., Oct. 20, 1997, at A1; The Bright Young Men Behind the Bench, U.S. News & World Rep., July 12, 1957, at 45; David Lauter, Clerkships: Picking the Elite, Nat’l L.J., Feb. 9, 1987, at 1; Linda Mathews, Supreme Court Clerks: Fame in a Footnote, L.A. Times, Jan. 5, 1972, at A1 (considering the stature of clerks, described by one source as “law school all-Americans”); see also infra notes 10-16 and accompanying text. After graduation, they likely clerked for one of the 179 active U.S. Court of Appeals judges, preferably one who has a reputation for sending clerks to the Court. 10 See, e.g., Edward Lazarus, Closed Chambers: The First Eyewitness Account of the Epic Struggles Inside the Supreme Court 19 (1st ed. 1998) (defining “feeder judges” as an “elite group” of “mostly appellate judges with track records of having their clerks land subsequent clerkships at the Supreme Court”); Lawrence Baum & Corey Ditslear, Supreme Court Clerkships and “Feeder” Judges, 31 Just. Sys. J. 26, 29, 43 (2010) [hereinafter Baum & Ditslear, Clerkships and “Feeder” Judges] (comparing a simulated random distribution of Supreme Court clerks across courts of appeals judges with the actual distribution and concluding that “the feeder system perceived by observers . . . certainly exists, in that a small proportion of court of appeals judges contribute a highly disproportionate number of clerks to the Court”).

Many students satisfy these criteria. As a rough cut, this group includes pretty much any student selected to clerk for a federal court of appeals judge, amounting to at least 800 qualified candidates. 11 The United States Courts of Appeals have 179 authorized judgeships. 28 U.S.C. § 44(a) (2018) (listing the number of judgeships for each circuit, including the eleven numbered circuits, the D.C. Circuit, and the Federal Circuit). The number of vacant seats (and thus clerkships) is more than offset by the large number of senior judges who still hear cases and thus are eligible to hire clerks. See Status of Article III Judgeships—Judicial Business 2021, U.S. Cts., https://www.uscourts.gov/statistics-reports/status-article-iii-judgeships-judicial-business-2021 [https://perma.cc/45NM-GGM4] (last visited Aug. 10, 2023) (counting 78 total vacancies and 494 senior judges). Given those numbers, we estimate more than 800 clerkships are available every year in the federal appellate court system. In addition to being highly qualified, those appellate clerks also have signaled their commitment to clerking through their investment in the intense selection process and their willingness to accept a relatively low salary. 12 Federal judicial law clerks are paid based on the Judiciary Salary Plan. The Plan sets pay based on whether the clerk has post-graduate legal experience, is admitted to a state bar, or lives in a high-cost metropolitan area. Qualifications, Salary, and Benefits, OSCAR, https://oscar.uscourts.gov/qualifications_salary_benefits [https://perma.cc/VH6L-DZXU] (last updated Apr. 26, 2023). In 2023, the base pay rate for a new law graduate without prior legal experience is $59,319. See id. (stating that law school graduates with no legal work experience are hired at grade JSP-11); see also Judicial Salary Plan Base Pay Rates – Table 00, U.S. Cts. (Jan. 2, 2023), https://www.uscourts.gov/ sites/default/files/archive_3/jsp_base_pay_rates-table_00_2023.pdf [https://perma.cc/N68S-9P26] (setting base pay for grade 11 at $59,319). A new law school graduate who is clerking for a federal circuit or district judge in New York City, however, would earn an annual salary of $80,769, reflecting a 36.16% locality payment. See Judicial Salary Plan: New York-Newark, NY-NJ-CT-PA – Table NY, U.S. Cts. (Jan. 2, 2023), https://www.uscourts.gov/sites/default/files/archive_3/jsp_new_york_2023.pdf [https://perma.cc/7SDV-VJZJ] (setting pay for the same grade at $80,769). By comparison, the median first-year associate base salary at private firms in 2023 is $200,000 nationwide and $215,000 in New York City. Findings on First-Year Salaries From the 2023 Associate Salary Survey, NALP (June 2023), https://www.nalp.org/0623research [https://perma.cc/4V5R-7J6G]. Of course, prospective Supreme Court clerks could opt to work at an elite firm, earning a starting salary of $250,000 plus a bonus. See Staci Zaretsky, Elite Firm Increases Associate Starting Salaries to $250k, Above the L. (June 14, 2023), https://abovethelaw.com/2023/06/brewer-2023-raise/ [https://perma.cc/X3G9-9KH8]. Thus, the odds for clerking on the Court remain low—below 1 in 20—even as candidates edge closer to the top.

This Piece is part of a larger project to understand how the top echelons of the legal profession are constructed. Top lawyers earn the most money, do the most deals, run corporations, and rule courts and legislatures. As a result, they have the most influence on national policy and exercise inordinate control over the origin, development, and enforcement of law. Thus, it is vital to understand who is chosen for the top law jobs, as well as how they are chosen. And, if the most coveted jobs go disproportionately to a particular subset of the participants, that’s important to know, given the multiplied social impact of those jobs. 13 For other projects in this vein, see generally Stephen J. Choi, Mitu Gulati & Eric A. Posner, The Role of Competence in Promotions From the Lower Federal Courts, 44 J. Legal Stud. S107 (2015) (exploring the role of competence levels on judicial promotions); Stephen J. Choi, Mitu Gulati & A.C. Pritchard, Should I Stay or Should I Go? The Gender Gap for Securities and Exchange Commission Attorneys, 62 J.L. & Econ. 427 (2019) (analyzing the gender gap among attorneys employed by the SEC); Tracey E. George, Mitu Gulati & Albert Yoon, Gender, Credentials, and M&A, 48 BYU L. Rev. 723 (2022) (examining the underrepresentation of women leading corporate M&A deals); Tracey E. George & Albert H. Yoon, The Labor Market for New Law Professors, 11 J. Empirical Legal Stud. 1 (2014) (surveying the factors that influence new professor hires at U.S. law schools); Tracey E. George & Albert H. Yoon, Measuring Justice in State Courts: The Demographics of the State Judiciary, 70 Vand. L. Rev. 1887 (2017) (addressing the knowledge gap on the demographics of state judges).

While much is written about Supreme Court clerkships, there is little in the way of systematic analysis of Court clerkships as an institution. This paucity is astonishing given the perceived importance clerks have in the work of the Court. Whether allegedly drafting 14 Chief Justice William Rehnquist started the most interesting kerfuffle. He was moved to write following his own Court clerkship. He shared his dismay over what he perceived as undue influence by liberal clerks within the drafting process. See Rehnquist, Who Writes Decisions, supra note 3, at 75. Rehnquist’s piece prompted other respected leaders within the legal field to weigh in on the discussion, including former Supreme Court law clerk William D. Roger and Yale law professor Alexander Bickel. Alexander M. Bickel, The Court: An Indictment Analyzed, N.Y. Times Mag., Apr. 27, 1958, at 16, 16 (“[T]heir political views and emotional preferences . . . make no discernable difference to anything in their work . . . [and,] as a group[,] the law clerks will no more fit any single political label than will any other eighteen young Americans who are not picked on a political basis.”); William D. Rogers, Do Law Clerks Wield Power in Supreme Court Cases?, Opinion, U.S. News & World Rep., Feb. 21, 1958, at 114, 114 (responding to Rehnquist’s article by explaining that Rogers’s experience clerking concurrently to Rehnquist for a different Justice evidenced that clerks tended to be politically moderate and that their political leanings did not influence the Justices’ votes). Of course, Rehnquist was not the only observer to imagine clerks were playing a sizable role within the Court. See Tom C. Clark, Internal Operation of the United States Supreme Court, 43 J. Am. Judicature Soc’y 45, 48 (1959) (quoting Justice Robert Jackson as observing that “[a] suspicion has grown at the bar that the law clerks . . . constitute a kind of junior court which decides the fate of the certiorari petitions”). (or leaking 15 When the draft opinion in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Org. was leaked, see Josh Gerstein & Alexander Ward, Supreme Court Has Voted to Overturn Abortion Rights, Draft Opinion Shows, Politico (May 2, 2022), https://www.politico.com/news/2022/05/02/supreme-court-abortion-draft-opinion-00029473 [https://perma.cc/32TG-DSJC], many social media posts accused law clerks of being the leakers, see Paul Blumenthal, Who Leaked the Supreme Court Draft? Here Are 4 Theories, HuffPost (May 3, 2022), https://www.huffpost.com/entry/supreme-court-roe-v-wadeleak_n_6271a2b0e4b01131b1285f02 [https://perma.cc/T244-VBTW] (sharing that two of the most common theories about the leak implicate Supreme Court law clerks); Will Sommer, MAGA Pundits Target Random Supreme Court Clerks After Roe Leak, Daily Beast (May 4, 2022), https://www.thedailybeast.com/maga-pundits-target-random-supreme-court-clerks-after-roe-leak [https://perma.cc/J4PL-VMMD] (detailing the viral reactions of conservative commentators accusing a law clerk of the leak). The Supreme Court Office of the Marshal “found nothing to substantiate” the allegations that law clerks were responsible for the leak. Press Release, Office of the Marshal, Sup. Ct. of the U.S., Marshal’s Report of Findings and Recommendations (Jan. 19, 2023), https://www.supremecourt.gov/publicinfo/press/Dobbs_Public_Report_January_19_2023.pdf [https://perma.cc/NQR4-TEPS]; see also Jodi Kantor, Inside the Supreme Court Inquiry: Seized Phones, Affidavits and Distrust, N.Y. Times (Jan. 21, 2023), https://www.nytimes.com/2023/01/21/us/supreme-court-investigation (on file with the Columbia Law Review) (questioning the logic of the accusations against clerks in light of the far-reaching reputational risks to these young lawyers). ) the Justices’ opinions, clerks regularly emerge as key actors in one of the nation’s most powerful institutions. Cynical outsiders may wonder whether part of the lack of information about this institution is by design. Many of the actors involved—elite law schools from which these clerks are selected, professors whose recommendations are key to their selection, and former clerks themselves—have an interest in preserving the mystique and secrecy. While a more innocuous explanation might be coordination failure or path dependence, it is ludicrous that this credential, which might be the ticket to ultimate money, power, and influence in the legal profession, is shrouded in mystery, even though its pathways are purportedly egalitarian institutions. Although a Court clerkship is a government job, none of the key actors involved appear interested in providing information about the process.

The limited existing literature primarily examines where clerks come from, focusing on their race, gender, and political affiliations.

16

One aspect that has received some attention is the gender gap. See generally David H. Kaye & Joseph L. Gastwirth, Where Have All the Women Gone? The Gender Gap in Supreme Court Clerkships, 49 Jurimetrics 411 (2009) (examining the flow of aspiring clerks from law school to the Justices’ chambers in recent years to locate bottlenecks that lead to the Supreme Court clerk gender gap); Tony Mauro, Diversity and Supreme Court Law Clerks, 98 Marq. L. Rev. 361 (2014) (“The percentage of clerks who are

women has gone from about one-quarter to one-third.”); Sarah Isgur, The New Trend Keeping Women Out of the Country’s Top Legal Ranks, Politico (May 4, 2021), https://www.politico.com/news/magazine/2021/05/04/women-supreme-court-clerkships-485249 [https://perma.cc/E86J-4RNY] (discussing how the assumption that one must complete multiple lower-level clerkships before clerking at the Supreme Court may make Supreme Court clerkships even less obtainable for women who want to have children or have incurred substantial law school debt).

But the justification for studying those characteristics has mostly been that those who get this scarce set of jobs likely have immense influence on the Justices and their decisions

17

See Todd C. Peppers, Courtiers of the Marble Palace: The Rise and Influence of the Supreme Court Law Clerk 10 (2006) (“My goal is both to provide the missing comprehensive historical treatment of the clerkship institution and to place the influence debate within the framework of principal agent theory.”); see also Mark C. Miller, Law Clerks and Their Influence at the US Supreme Court: Comments on the Recent Works by Peppers and Ward, 39 L. & Soc. Inquiry 741, 742 (2014).

—“legal Rasputins” in the words of one scholar.

18

See Adam Bonica, Adam Chilton, Jacob Goldin, Kyle Rozema & Maya Sen, Legal Rasputins? Law Clerk Influence on Voting at the US Supreme Court, 35 J.L. Econ. & Org. 1, 1 (2019).

For example, studies of clerkship classes reveal that most Supreme Court clerks have been white men and that Justices tend to give clerkships to those who have similar political affiliations to their own (or who clerk for lower court judges with those affiliations).

19

See, e.g., Adam Bonica, Adam S. Chilton, Jacob Goldin, Kyle Rozema & Maya Sen, Measuring Judicial Ideology Using Law Clerk Hiring, 19 Am. L. & Econ. Rev. 129, 135–38 (2017); Corey Ditslear & Lawrence Baum, Selection of Law Clerks and Polarization in the U.S. Supreme Court, 63 J. Pol. 869, 871 (2001) [hereinafter Ditslear & Baum, Selection of Law Clerks].

But what does it take to get these clerkships, and how do they matter to one’s subsequent career? Only one prior study, from over a decade ago, has analyzed this question, and it showed how clerkships once led primarily to government and universities but increasingly lead to law firms and corporations. 20 Nelson et al., The Liberal Tradition, supra note 6, at 1780–-91 (positing that post-clerkship career trends—namely, fewer professors and more corporate lawyers—“support[] the claim that the recent hiring of clerks by conservative Justices has taken on an increasingly partisan character . . . [that] correlate[s] strongly with significant new trends in the careers of law clerks once they leave the Court”). If Court clerks hold outsized influence in the upper echelons of policy and law, additional analysis and transparency are necessary.

Part I of this Piece explores the Supreme Court clerkship market and begins with the people who hold the positions of interest: Supreme Court clerks. Specifically, what attributes do they share, and, just as important, what unites the legions of law graduates who did not clerk? To build on this question, the Part then looks at the universe of law students from a single school that holds a special place in the history of clerkships: Harvard Law School. Next, with an eye to longer-term outcomes of Court clerks, Part II examines the fall 2021 labor market participation of clerks who served between 1980 and 2020 and considers whether Court clerkships act as an equalizer between clerks of different educational backgrounds, genders, and ethnicities.

I. The Supreme Court Clerkship Market

Pursuant to Article III, Congress established the U.S. Supreme Court in 1789 21 Judiciary Act of 1789, ch. 20, §§ 1, 13, 1 Stat. 73, 73, 81 (creating, pursuant to Article III of the U.S. Constitution, a Supreme Court with one Chief Justice and five Associate Justices and granting the Court jurisdiction over appeals from larger civil cases decided in lower federal courts and state court decisions on federal statutes). but only provided funding for law clerks in 1886. 22 Act of Aug. 4, 1886, ch. 902, 24 Stat. 254 (providing “for stenographic clerk for the Chief Justice and for each associate Justice of the Supreme Court, at not exceeding one thousand six hundred dollars each”). Justice Horace Gray, however, introduced the clerk practice four years earlier when he joined the Supreme Court from the Massachusetts high court. 23 For a thorough and oft-relied-upon history of the institution as well as the specific role of Justice Gray, see generally Chester A. Newland, Personal Assistants to Supreme Court Justices: The Law Clerks, 40 Or. L. Rev. 299 (1961) (providing a history of the Supreme Court law clerk). For a first-hand account from one of Gray’s former clerks, see Samuel Williston, Life and Law 87 (1940) (explaining that his “task was to aid Judge Gray in his preparation of cases to be voted on . . . and in his writing of the opinions that were assigned to him”). Gray hired and personally paid for a top Harvard Law graduate to serve as a one-year law clerk. 24 See John R. Schmidhauser, The Supreme Court: Its Politics, Personalities, and Procedures 119 (1960) (describing Gray’s role in introducing the practice of hiring recent law graduates as clerks). His colleagues also hired clerks; once Congress paid, however, they relied on the clerks as secretaries rather than as research assistants. 25 Todd C. Peppers & Clare Cushman, Introduction to Of Courtiers & Kings: More Stories of Supreme Court Law Clerks and Their Justices 7, 7 (Todd C. Peppers & Clare Cushman eds., 2015) (explaining early clerks “worked long hours for low pay and assumed tedious duties that were mainly secretarial in nature—including taking dictation, typing up opinions, cutting and pasting revisions, and performing nonjudicial tasks (such as paying bills and balancing checkbooks) for their justices”). Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, who succeeded Justice Gray, continued the practice of hiring a Harvard Law graduate specifically to assist with legal research. 26 See Paul R. Baier, The Law Clerks: Profile of an Institution, 26 Vand. L. Rev. 1125, 1129–30 (1973) (providing a timeline of the practice). Justice Louis Brandeis and Justice Felix Frankfurter effectively institutionalized hiring recent law graduates as legal researchers, ending the clerk-stenographer model that dominated prior to 1940. 27 Nelson et al., The Liberal Tradition, supra note 6, at 1761–63; see also Karl N. Llewellyn, The Common Law Tradition: Deciding Appeals 321 (1960) (considering the law clerk practice and finding it to be “Frankfurter’s greatest contribution to our law that his vision, energy, and persuasiveness turned this two-judge [Gray and Holmes] idiosyncrasy into what shows high possibility of becoming a pervasive American legal institution”). Thus, the modern Court clerkship is more than 80 years old.

Federal judges routinely delegate important tasks to others—but not the annual selection of judicial law clerks.

28

For example, U.S. district judges rely heavily on U.S. magistrate judges but delegate to a committee the job of vetting magistrate judge applicants and recommending five for the post. See Christina L. Boyd, Tracey E. George & Albert H. Yoon, The Emerging Authority of Magistrate Judges Within U.S. District Courts, 10 J.L. & Cts. 37, 47, 57 (2022) (describing the selection process and demonstrating the substantial reliance of district judges on magistrate judges). Other high courts, such as the Supreme Court of Canada, have a centralized application and screening process that channels candidates to the judges. See, e.g., Law Clerk Program, Sup. Ct. of Can., https://www.scc-csc.ca/empl/lc-aj-eng.aspx [https://perma.cc/6QC7-7CSU] (last visited Aug. 10, 2023) (promulgating the Canadian Supreme Court’s application process).

Even during an era of larger dockets, Supreme Court Justices reported clerkship selection to be a priority.

29

One exception was that most first-year Justices would hire some or all of their clerks from the pool of former or current Justices’ recent clerks rather than launching a full-scale selection process. See, e.g., John C. Jeffries, Justice Lewis F. Powell, Jr., and the Era of Judicial Balance 241–42 (1994) (describing how Powell, who took the seat of recently deceased Justice Hugo Black, asked two of Black’s clerks to stay on).

Chief Justice William Rehnquist claimed that he “spen[t] a fair amount of time picking [his] law clerks each year, because having good law clerks is a very important factor in the proper functioning of [his] chambers.”

30

William H. Rehnquist, The Supreme Court: How It Was, How It Is 262 (1987);

see also Patricia M. Wald, Selecting Law Clerks, 89 Mich. L. Rev. 152, 153 (1990) (explaining that “an excellent versus mediocre team of clerks makes a huge difference in the judge’s daily life and in her work product”); cf. Adam Liptak, Justices Are Long on Words but Short on Guidance, N.Y. Times (Nov. 17, 2010), https://www.nytimes.com/2010/11/18/us/18rulings.html (on file with the Columbia Law Review) (discussing anecdotes and analytics suggesting Justices rely on clerks to prepare draft opinions).

Rehnquist’s colleague Justice Lewis Powell described choosing law clerks as “among the most important decisions he made during a term.”

31

J. Harvie Wilkinson III, Serving Justice: A Supreme Court Clerk’s View 89–90 (1974).

Despite the importance of the decision, we know little about what Justices look for in their law clerks. Core work consists of assisting the Justice with researching and, in some cases, drafting opinions and helping sort through petitions for certiorari. But, formally, this is all work assisting the Justices; the Justices make the decisions. Top students from every law school, especially after a year or so of training at the lower courts, should be able to provide the necessary support work. And indeed, were they looking for critical insights and advice, the Justices should prefer clerks with more experience or hire them to work for more than a single year so they could develop it. 32 For research into this question at the lower court level based on interviews with judges who have utilized both term and career clerks, see Donald W. Molloy, Designated Hitters, Bat Boys and Pinch Hitters: Career Clerks or Term Clerks, 82 Law & Contemp. Probs., no. 2, 2019, at 133, 135. As we demonstrate in more detail in this Piece, Justices do not choose clerks based solely—or even primarily—on the demonstration of the skills or knowledge central to their work. Instead, the evidence reveals that clerks, as a group, are chosen based on their elite institutional ties and networks.

To examine this market, we begin with the universe of Court clerks for the period from 1980 through 2020. Second, we explore selection of Court clerks by examining the universe of law students from Harvard Law, which, as we demonstrate below, has the attributes of (a) placing more clerks on the Court than any other school; and (b) providing granular information for each graduating student.

A. Cohort of Court Clerks

A comprehensive list of former Supreme Court clerks is readily available on Wikipedia. 33 List of Law Clerks of the Supreme Court of the United States, Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lists_of_law_clerks_of_the_Supreme_Court_of_the_United_States [https://perma.cc/V5MF-MZFR] (last visited Aug. 10, 2023). The clerks, themselves, keep this information available because it is a credential that persists in public biographies even as other dated credentials fall off the curriculum vitae. Moreover, the nature of Wikipedia increases the credibility of the list: Any missing clerk will likely flag the oversight, and any clerks who spot a false positive or negative will also submit a revision. Finally, we were able to review the list for consistency with other available lists of clerks and concluded it was a reliable list that has the added advantage of being publicly available.

Wikipedia catalogs the clerks corresponding to each seat on the Court. 34 Supreme Court seats are numbered by the order in which they were originally created. The Judiciary Act of 1789 established six seats of the U.S. Supreme Court. Judiciary Act of 1789, ch. 20, 1 Stat. 73. The Court expanded the number of Justices as the number of federal judicial circuits increased to reflect additional states joining the union. See Seventh Circuit Act of 1807, ch. 16, 2 Stat. 420; Eighth and Ninth Circuits Act of 1837, ch. 34, 5 Stat. 176; Tenth Circuit Act of 1863, ch. 100, 12 Stat. 794. It also contracted at times—Judicial Circuits Act of 1866, ch. 210, 14 Stat. 209; Judicial Circuits Act of 1869, ch. 22, 16 Stat. 44—to achieve its current number of nine Justices. For each clerk, Wikipedia provides the clerk’s name, their law school and years attended, and previous judicial clerkship (if any). We chose 1980 through 2020 as our period of interest because those who clerked during this period would likely range in age from 26 through 66—old enough to have embarked on their post-clerkship legal career, and young enough to still be working. This produced a list of 1,424 former clerks, including those clerking for both sitting and retired Justices.

We verified each of the clerks’ participation on the Court through printed or online sources (e.g., employer websites or LinkedIn). From these sources, we supplemented the data with additional information: gender, 35 Clerks’ binary gender was imputed based on first names provided by the Social Security Administration along with Australian, Canadian, and UK government sources. See Gender by Name, U.C. Irvine Mach. Learning Repository (Mar. 14, 2020), https://archive.ics.uci.edu/ml/datasets/Gender+by+Name (spreadsheet on file with the Columbia Law Review). Coders then compared the imputed gender to information on public sources, such as pronouns, affiliations, and photos, as a check on the imputation. ethnicity, 36 We determined each clerk’s ethnicity through the same two-stage process as we used for gender: First, we relied on the U.S. Census to identify which surnames disproportionately represented people of a certain race or ethnicity. See Frequently Occurring Surnames From the 2010 Census, U.S. Census (Oct. 8, 2021), https://www.census.gov/topics/population/genealogy/data/2010_surnames.html [https://perma.cc/PD7R-MQWQ]. We imputed a particular ethnicity if the fraction of the population exceeded 75%. We again turned to self-identification through biographical sources to check the imputed race/ethnicity and also to fill any gaps, if possible. undergraduate education, and indicators of academic performance.

At the outset, we were interested in three characteristics of the law clerks: (1) their gender and ethnicity; (2) their academic credentials; and (3) their previous clerkships. We examine these in turn.

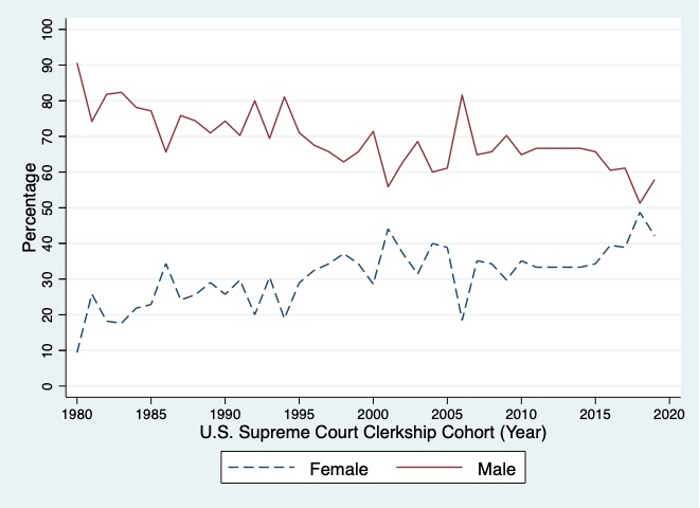

Gender and Ethnicity. — Males comprise 69% (n=983) of the Court’s clerks over the selected forty-year period. Figure 1 shows the breakdown by year. The time trends indicate gradual but steady increases in the proportion of female clerks on the Court. At the same time, the most recent years indicate a gap where men still constitute nearly 60% of Court clerks. This pattern takes on more significance considering the gender trends in law schools during this period. Women made up 39% of all law students during the 1980s, more than 40% during the 1990s, and 45% during the 2000s. 37 See Women in the Legal Profession, ABA, https://www.abalegalprofile.com/women.php (on file with the Columbia Law Review) (last visited Aug. 30, 2023) (showing the male–female composition in U.S. law schools, with additional statistics from earlier years). Over the past decade, women have steadily increased their enrollment relative to men: Female law students exceeded the number of male law students for the first time in 2016. 38 See Elizabeth Olsen, Women Make Up Majority of U.S. Law Students for First Time, N.Y. Times: Dealbook (Dec. 16, 2016), https://www.nytimes.com/2016/12/16/business/dealbook/women-majority-of-us-law-students-first-time.html (on file with the Columbia Law Review). In 2021, women were 55% of all law students, 39 See Women in the Legal Profession, supra note 37. yet the number of women Court clerks lags behind the number of men Court clerks.

Figure 1. Gender Composition of Court Clerks

1980–2020

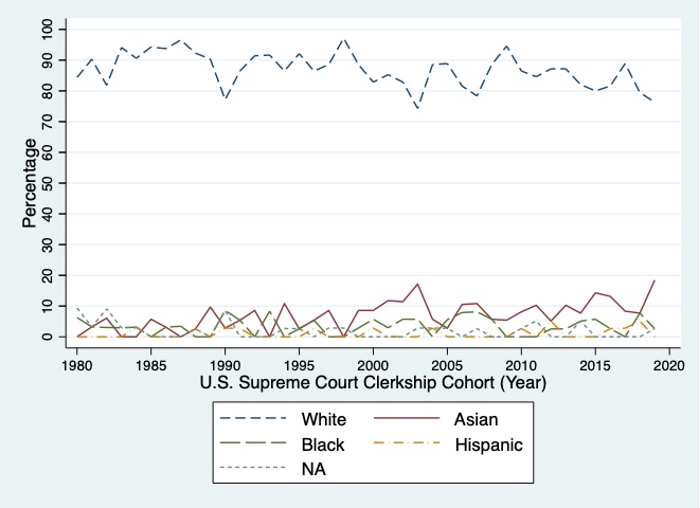

Over the entire period, 87% (n=1236) of clerks were white. Of the remaining 13% (n=188), 100 were Asian or Pacific Islander, 48 were Black, 14 were Hispanic, and 26 could not be identified. 40 We identified a single ethnicity for each clerk using the technique described supra note 36, although we recognize that some clerks may identify with or be most accurately described as having multiple ethnicities. Figure 2 provides the breakdown of Court clerks by ethnicity by year. The trends show that the percentage of white clerks has a modest downward trend, with considerable variation from year to year. As the aggregate numbers suggest, Asian or Pacific Islanders represent the greatest increase in non-white clerks.

Looking at the intersection of gender and ethnicity, we find recurring patterns across most subgroups, with one outlier. Among white, Hispanic, and Asian-Pacific clerks, the fraction of women ranged from 21% (Hispanics) to 30% (whites). In contrast, Black clerks were evenly divided between male and female.

Figure 2. Ethnic Composition of Court Clerks

1980–2020

Academic Credentials. — While the Court draws attention primarily for the opinions it publishes, the personal biographies of the Justices also generate considerable interest. The story typically unfolds as follows: The Justices are highly accomplished, having achieved professional success prior to their appointment to the Court. For the last 70 years, most serving Justices attended an elite law school—primarily Harvard or Yale. 41 Patrick J. Glen, Harvard and Yale Ascendant: The Legal Education of the Justices from Holmes to Kagan, 58 UCLA L. Rev. Discourse 129, 136–37 (2010), https://www.uclalawreview.org/pdf/discourse/58-7.pdf [https://perma.cc/823G-FHZX]; see also Benjamin Barton, An Empirical Study of Supreme Court Justice Pre-Appointment Experience, 64 Fla. L. Rev. 1137, 1168–70 (2012) (describing the educational background of Supreme Court Justices); Noah Feldman, Opinion, There’s a Lot of Harvard and Yale on the Supreme Court. And That’s OK., Bloomberg (Aug. 7, 2022), https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2022-08-07/harvard-and-yale-have-a-lock-on-conservative-supreme-court?sref=jmiDULpC (on file with the Columbia Law Review) (describing the educational background of the current Justices). Correspondingly, a large fraction of Court clerks attend these same elite law schools. 42 See, e.g., Adam Liptak, A Well-Traveled Path From Ivy League to Supreme Court, N.Y. Times (Sept. 6, 2010), https://www.nytimes.com/2010/09/07/us/politics/07clerkside.html (on file with the Columbia Law Review) (describing how law graduates from a small number of law schools account for the majority of Court clerkships and quoting Justice Antonin Scalia as saying that “[b]y and large, . . . I’m going to be picking from the law schools that basically are the hardest to get into”). And, with increasing frequency, Supreme Court Justices are former clerks themselves. 43 The Supreme Court official website notes that six of the nine current Justices—Ketanji Brown Jackson, Amy Coney Barrett, Brett M. Kavanaugh, Neil M. Gorsuch, Elena Kagan, and (Chief Justice) John Roberts—were former Court clerks. FAQ – Supreme Court Justices, Have Any Supreme Court Justices Served as Law Clerks?, Sup. Ct. of the U.S., https://www.supremecourt.gov/about/faq_justices.aspx [https://perma.cc/M7BC-38T3] (last visited Aug. 10, 2023).

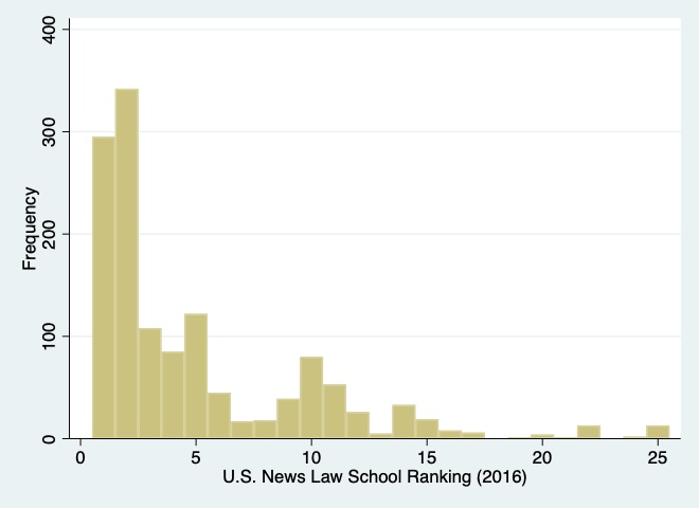

The data allow us to examine clerks’ law school education more closely. We found that 94% (n=1335) of clerks attended a school ranked among the top twenty-five (the “T25”), based on the 2016 U.S. News & World Report Law School Rankings. 44 We chose this year because it fell within the period when U.S. News & World Report provided ordinal rankings for most law schools accredited by the American Bar Association (150 out of roughly 200). While rankings for individual schools move up or down from year to year, most changes are modest, particularly among the highest-ranked schools, from which most Justices select their clerks. See Michael C. Macchiarola & Arun Abraham, Options for Student Borrowers: A Derivatives-Based Proposal to Protect Students and Control Debt-Fueled Inflation in the Higher Education Market, 20 Cornell J.L. & Pub. Pol’y 67, 91 (2010) (“[L]aw school rankings largely remain stable over time . . . .” (quoting Rachel F. Moran, Of Rankings and Regulation: Are the U.S. News & World Report Rankings Really a Subversive Force in Legal Education? 81 Ind. L.J. 383, 383 (2006))). A closer look supports anecdotal accounts of the primacy of a few schools. Figure 3, providing the breakdown by school (based on rank), reveals that Yale and Harvard account for 45% of all law clerks. These two schools, along with Stanford, Columbia, and Chicago (which together were the top five law schools during this period), account for over two-thirds of all law clerks. The top fourteen (the “T14”) schools together account for 86% of clerks.

Figure 3. Law Schools From Which Court Clerks Graduated

1980–2020

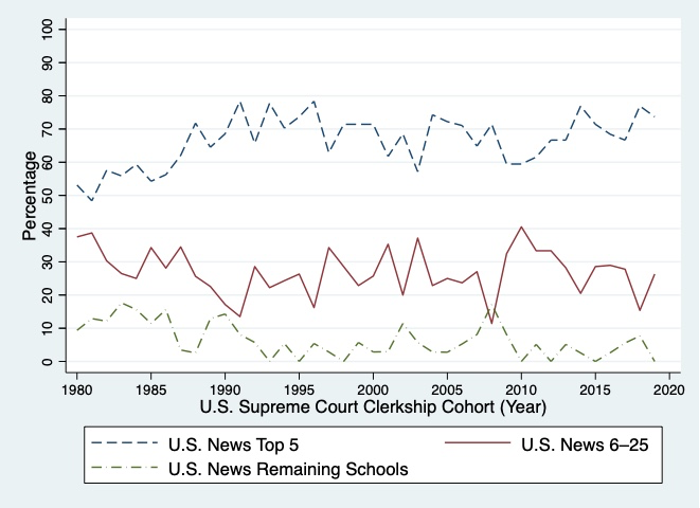

The distribution of represented select law schools, as shown in Figure 4, shows little variation over time. If anything, the concentration of clerks from the five highest-ranked law schools has increased slightly over the years. Schools ranked six to twenty-five have—with the exception of 2008—contributed more clerks than the remaining law schools. The emphasis on graduates from the most selective schools during this period reflects preference among all Justices, with only modest variation. For example, during this period, Chief Justice Roberts chose fifty-eight clerks: thirty-seven clerks from Yale or Harvard, and only one from outside the T25 (Georgia). Justice Sotomayor, among her forty-six clerks, selected twenty-one from Harvard or Yale and two from outside the T25 (Brooklyn and Hawaii). Even Justice Thomas, who has a reputation of hiring across a range of law schools, 45 See, e.g., Molly McDonough, Critical of Law School Rankings, Thomas Says ‘Ivies’ OK, but He Prefers Hiring ‘Regular’ Students, ABA J. (Sept. 24, 2012), https://www.abajournal.com/news/article/critical_of_law_school_rankings_thomas_says_ivies_ok [https://perma.cc/H4LN-8E5K]. chose over half his 119 clerks from Yale, Harvard, or Chicago (n=62) and only fifteen clerks from law schools outside the T25.

Figure 4. Annual Composition of Law Schools From Which Court Clerks Graduated

1980–2020

Previous Judicial Clerkships. — The relevance of prior judicial clerkships for clerking on the Supreme Court has evolved over time, reflecting both institutional norms and preferences of individual Justices. Until the late nineteenth century, Justices did not hire law clerks. 46 Newland, supra note 23, at 305–06. At the inception of clerkships as an institution, most law clerks took their position on the Court without having clerked previously for a lower federal court judge or a state judge. 47 Peppers & Cushman, supra note 25, at 1 (describing early clerks as either “older professional stenographers who served for years or decades at the Court, or younger men who juggled their clerkship duties with law school studies at night”). By the 1950s, most Justices began hiring clerks who had previously clerked for another judge. 48 Nelson et al., The Liberal Tradition, supra note 6, at 1762 (explaining that “[a]ll of [President] Roosevelt’s appointees adopted Brandeis’s practice of appointing young law school graduates as their clerks” and the practice of stenographer clerks faded when the final non-Roosevelt appointees retired). Justices, however, also hired clerks without a previous clerkship. For example, John Hart Ely, who later became author of Democracy and Distrust and a tenured faculty member at Harvard, Yale, and Stanford law schools, was selected by Chief Justice Warren upon graduating from Yale Law School. 49 See Adam Liptak, John Hart Ely, a Constitutional Scholar, Is Dead at 64, N.Y. Times (Oct. 27, 2003), https://www.nytimes.com/2003/10/27/us/john-hart-ely-a-constitutional-scholar-is-dead-at-64.html (on file with the Columbia Law Review) (recounting that Ely, after graduating from Yale Law, “served as the youngest staff member of the Warren Commission, which investigated the assassination of President John F. Kennedy,” and then went on to clerk for Chief Justice Earl Warren).

By the 1980s, the Court developed a strong, almost categorical norm of hiring clerks who previously clerked. The previous clerkship was often for an Article III appellate court (e.g., First Circuit Court of Appeals, D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals). The data reveal that, increasingly, Court clerks have completed multiple clerkships prior to clerking on the Supreme Court: Two hundred twenty-six clerks had completed two clerkships, and three clerks had completed three clerkships.

In recent years, commentators such as David Lat have begun explicitly discussing the phenomenon of the “feeder judge.” 50 See, e.g., David Lat, Supreme Court Clerk Hiring Watch: Up-And-Coming Feeder Judges, Original Jurisdiction (Dec. 16, 2022), https://davidlat.substack.com/p/supreme-court-clerk-hiring-watch-c46 [https://perma.cc/EWR7-EBBX]; see also Baum & Ditslear, Supreme Court Clerkships and “Feeder” Judges, supra note 10, at 26 (finding that clerks from a small number of federal appellate judges are subsequently chosen by the Supreme Court); Alexandra Hess, The Collapse of the House that Ruth Built: The Impact of the Feeder System on Female Judges and the Federal Judiciary, 1970–2014, 24 Am. U. J. Gender Soc. Pol’y & L. 61, 62 (2014). This is a concept the authors remember hearing in law school in the 1990s: An appellate clerkship on a prestigious circuit, such as the D.C. Circuit, improved one’s chances for a Court clerkship. 51 For informal discussion of these chances, see Adam Liptak, A Sign of the Court’s Polarization: Choice of Clerks, N.Y. Times (Sept. 6, 2010), https://www.nytimes.com/2010/09/07/us/politics/07clerks.html (on file with the Columbia Law Review) [hereinafter Liptak, Sign of Court’s Polarization] (describing how Justices tend to hire clerks from feeder judges who share their ideology); Dahlia Lithwick, Who Feeds the Supreme Court?, Slate (Sept. 14, 2015), https://slate.com/news-and-politics/2015/09/supreme-court-feeder-judges-men-and-few-women-send-law-clerks-to-scotus.html [https://perma.cc/HF9S-SECW] (examining how diversity among feeder judges may impact Supreme Court clerk diversity); Josh Blackman, Which Circuit Judges and Circuits Courts Feed the Most SCOTUS Clerks, Reason: The Volokh Conspiracy (Aug. 12, 2021), https://reason.com/volokh/2021/08/12/which-circuit-judges-and-circuit-courts-feed-the-most-scotus-clerks/ [https://perma.cc/LFA9-D4S9] (providing a breakdown of the top feeder judges and circuit courts). Our data suggest that there were individual judges who have had special feeder powers going back many decades. Nevertheless, conventional wisdom is that individual judges and their politics matter more today. 52 Liptak, Sign of Court’s Polarization, supra note 51. Systematic data on this trend, David Lat’s valiant efforts notwithstanding, have been lacking.

Given the competition to become a Court clerk, it is unsurprising that the aspiring clerks would seek a lower court clerkship that would maximize their chances of being selected by the Supreme Court. Judges also respond to these incentives, with some appellate judges thought to select clerks based on their perceived chances of being subsequently selected by one of the Justices. 53 See Wald, supra note 30, at 154–55; Catherine Rampell, Judges Compete for Law Clerks on a Lawless Terrain, N.Y. Times (Sept. 23, 2011), https://www.nytimes.com/2011/09/24/business/judges-compete-for-law-clerks-on-a-lawless-terrain.html (on file with the Columbia Law Review).

Our data show robust evidence of the feeder judge phenomenon. We constructed our measure of feeder judges in the following way. Our cohort of 1,424 Court clerks participated in 1,666 lower court clerkships (reflecting the trend for multiple lower court clerkships among recent clerks). Supreme Court clerks previously clerked for 332 unique judges. We rank-ordered these lower court judges, based on the number of their clerks who subsequently clerked on the Court. We then used different cut-offs for our list of feeder judges based on different percentages, as reported in Table 1. For example, “Top 1%” corresponds to the three lower court judges (3/332) who sent the greatest number of their clerks to the Court.

Table 1. Influence of Select (“Feeder”) Judges

1980–2020

| Judge Placement of Own Clerks Onto U.S. Supreme Court | Total Clerks Sent to U.S. Supreme Court | Percentage of U.S. Supreme Court Clerks’ Previous Clerkships |

| Top 1% | 171 | 7% |

| Top 10% | 902 | 54% |

| Top 25% | 1254 | 75% |

| Top 50% | 1489 | 89% |

Across different cut-off levels, a select number of lower court judges produce a disproportionate number of Court clerks. The top 1% (three judges) comprised 7% of the clerks’ previous clerkships. The top 10% (thirty-three judges) comprised over 54% of all previous clerkships. The top quarter (eighty-three judges) represented three-quarters of all clerkships, and the top half (166 judges) represented 89% of all clerkships. And those are only the top half of the judges who sent any clerks to the Court between 1980 and 2020.

The prevalence of feeder judges depends on the chosen cut-off and decade. Table 2 provides a breakdown of Table 1 by decade. The top 1% (one judge) in each decade counted for 6% of Court clerks. During the 1980s, the top feeder was Judge J. Skelly Wright, who sent 18 of his clerks to the Court; during the 1990s, it was Judge Laurence Silberman, who sent 25; Judge Alex Kozinski sent 24 clerks to the Court during the 2000s, and then-Judge Brett Kavanaugh sent 34 of his clerks to the Court.

Table 2. Concentration of Select (“Feeder”) Judges by Decade

1980–2020

| Judge Placement of Own Clerks Onto U.S. Supreme Court | 1980s | 1990s | 2000s | 2010s |

| Top 1% | 6% | 6% | 6% | 6% |

| Top 10% | 34% | 43% | 43% | 49% |

| Top 25% | 60% | 69% | 71% | 71% |

| Top 50% | 83% | 84% | 87% | 87% |

| Unique Judges | 107 | 120 | 106 | 144 |

| Total Clerkships | 325 | 385 | 405 | 545 |

The larger differences over time occurred within the top decile and quartile of judges, respectively. In the 1980s, the top 10% (ten judges) accounted for roughly a third of all Court clerks. This group of jurists include notable former academics such as Richard Posner, as well as future Supreme Court Justices like Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Stephen Breyer. The percentage increased to 43% for each of the next two decades but grew to nearly half of all Court clerks by the 2010s. By comparison, the influence of the top half of judges grew modestly over this time (83% to 87%).

Notably, the increased concentration of feeder judges grew as more Court clerks completed multiple clerkships. The trend provides evidence of the importance of feeder judges, namely that those with a clerkship with a non-feeder judge could improve their chances of a Court clerkship by subsequently clerking for a feeder judge.

“Feeder faculty” are a known phenomenon at the top law schools: faculty who have cultivated deep relationships with feeder judges and even Supreme Court Justices. 54 Leah Litman & Deeva Shah, On Sexual Harassment in the Judiciary, 115 Mich. L. Rev. 599, 626–27 (2020) (describing the influence of certain feeder faculty at Yale Law School). Lore has long held that while references from most faculty are useless with respect to clerkships with feeder judges, a reference from a feeder faculty can be quite effective. 55 Ruggero J. Aldisert, Ryan C. Kirkpatrick & James R. Stevens III, Rat Race: Insider Advice on Landing Judicial Clerkships, 110 Penn St. L. Rev. 835, 835 n.4 (2006). But there is little actual data on this phenomenon that any institutions are willing to provide, even though a clerkship is government employment that potentially gives enormous benefits to those who get it. 56 One source of this information might be the public relations announcements that law schools such as the University of Virginia (UVA) put out on their students who receive Supreme Court clerkships. These announcements at UVA frequently report on which faculty the student is grateful to for helping them obtain the clerkship—and presumably some of those faculty are the key “feeders.” And there is a subset of faculty who appear more often in these announcements. But there is not enough data here for us to do any systematic analysis (we tried). For examples of these announcements, see, e.g., Press Release, Univ. of Va. Sch. of L., Erin Brown ‘21 to Clerk at U.S. Supreme Court (Jan. 26, 2023), https://www.law.virginia.edu/news/202301/erin-brown-21-clerk-us-supreme-court [https://perma.cc/C5M5-68U4]; Press Release, Univ. of Va. Sch. of L., Henry Dickman ‘20 to Clerk for U.S. Supreme Court Justice Amy Coney Barrett (May 2, 2022), https://www.law.virginia.edu/news/202205/henry-dickman-20-clerk-us-supreme-court-justice-amy-coney-barrett [https://perma.cc/2KE2-YUKA]; Press Release, Univ. of Va. Sch. of L., Rachel Daley ‘21 to Clerk for U.S. Supreme Court Justice Neil Gorsuch (Sept. 1, 2022), https://www.law.virginia.edu/news/202209/rachel-daley-21-clerk-us-supreme-court-justice-neil-gorsuch-0 [https://perma.cc/LA5X-77VK].

Even if data on feeder faculty are scant, ample data supports the benefits of common educational background between feeder judges and Court clerks. Table 3 reports the top three feeder judges (four if there were ties among the top three) for each of the past four decades, including the number of clerks sent to the Court; the judges’ own educational background; and whether they themselves clerked on the Court.

Two notable trends emerge. First, feeder judges’ backgrounds resemble those of eventual Court clerks: Yale and Harvard recur often, for both undergraduate and law school degrees; six feeder judges were former Court clerks themselves. 57 As an illustration of this pattern: Justice Kavanaugh clerked for Judge Alex Kozinski, a top feeder judge, prior to clerking for Justice Kennedy. Kavanaugh later became a top feeder judge before ascending to the Supreme Court himself. See Steven Calabresi, Opinion, Brett Kavanaugh and His Association With Alex Kozinski, The Hill (Aug. 12, 2018), https://thehill.com/opinion/judiciary/401468-brett-kavanaugh-and-his-association-with-alex-kozinski/ [https://perma.cc/8ACQ-TELU]. Second, these feeder judges have become increasingly active by the decade.

Table 3. Educational Background of Leading Feeder Judges

by Decade

1980–2020

| Decade | Judge | Court | Clerks Sent to U.S. Supreme Court | Undergrad | Law School | Clerked on U.S. Supreme Court |

| 1980s | J. Skelly Wright | D.C. Circuit | 17 | Loyola, New Orleans | Loyola, New Orleans | |

| 1980s | Abner J. Mikva | D.C. Circuit | 14 | Wash U. | U. Chicago | |

| 1980s | Harry T. Edwards | D.C. Circuit | 13 | Cornell | U. Michigan | |

| 1980s | James L. Oakes | 2nd Circuit | 13 | Harvard | Harvard | |

| 1990s | Laurence H. Silberman | D.C. Circuit | 25 | Dartmouth | Harvard | |

| 1990s | J. Michael Luttig | 4th Circuit | 22 | Washington & Lee | Virginia | Burger |

| 1990s | Alex Kozinski |

9th Circuit | 18 | UCLA | UCLA | Burger |

| 2000s | Alex Kozinski |

9th Circuit | 24 | UCLA | UCLA | Burger |

| 2000s | J. Harvie Wilkinson III | 4th Circuit | 22 | Yale | Virginia | Powell |

| 2000s | Merrick B. Garland | D.C. Circuit | 21 | Harvard | Harvard | Brennan |

| 2010s | Brett M. Kavanaugh | D.C. Circuit | 34 | Yale | Yale | Kennedy |

| 2010s | Merrick B. Garland | D.C. Circuit | 29 | Harvard | Harvard | Brennan |

| 2010s | Robert A. Katzmann | 2nd Circuit | 24 | Columbia | Yale |

Academic accolades of Court clerks warrant consideration yet cannot be reliably analyzed. The intuition is self-evident: Stronger performing students have a greater chance of clerking on the Court. However, academic transcripts cannot be observed, and proxy indicators of academic success (e.g., Phi Beta Kappa for undergraduates; or for law school, Order of the Coif 58 The Order of the Coif is an “honorary scholastic society . . . recognizing those who as law students attained a high grade of scholarship.” Order of the Coif, https://orderofthecoif.org/ [https://perma.cc/VED3-KSVB] (last visited Aug. 10, 2023). or membership on the flagship law review) are not consistently publicized by Court clerks. An even larger obstacle is that formal accolades are absent at the institutions from where many Court clerks are chosen: Harvard, Yale, and Stanford. While most ABA-accredited law schools are members of the national chapter of Order of the Coif, Harvard is not among them. 59 See Member Schools, Order of the Coif, https://orderofthecoif.org/member-schools [https://perma.cc/2DQD-Y7FT] (last visited Aug. 10, 2023). Moreover, Yale, one of the earliest members of the society, stopped nominating students in 1969. 60 See Email from Femi Cadmus, L. Libr. & Professor of L., Yale L. Sch., to authors (July 27, 2022) (on file with the Columbia Law Review). Stanford, after switching from a traditional grading (i.e., on a 4.3 scale) to an honors-pass system in 2008, discontinued its participation in the society. 61 See Email from Carol Wilson, L. Libr., Stanford L. Sch., to authors (Aug. 1, 2022) (on file with the Columbia Law Review).

B. Selection Into a Court Clerkship: A Study of Harvard Law School

The accomplishments of Supreme Court clerks provide incomplete insight into the intense competition for Court clerkships, in terms of both who wins and who loses. Among Article III (federal) courts, there are 179 court of appeals judges and 673 district judges. 62 Some authorized judgeships remain vacant while prospective nominees participate in the Senate confirmation process. For example, in September 2021, there were six appellate and seventy-two district vacancies. See U.S. Courts, Status of Article III Judgeships, supra note 11. While individual judges have some latitude over the composition of their chambers, most judges elect to have annual (rather than permanent) clerks. Appellate judges typically hire three to four clerks per year; district judges, two or three. In addition, many Article III judges (appellate and district) on senior status continue to hire clerks, 63 For example, in 2022, nineteen appellate judges and thirty-two district judges took senior status. See Biographical Directory of Article III Federal Judges, 1789–Present, Fed. Jud. Ctr., https://www.fjc.gov/history/judges/search/advanced-search [https://perma.cc/5FJH-9CHU] (last visited Aug. 10, 2023) (choose Senior Status / Termination from Search Criteria; then select Senior Status Date; then search between 2022-01-01 and 2022-12-31). the exact number of which depends on the judges’ caseload. Based on these numbers, Article III judges hire roughly 2,000 clerks annually.

The Court’s clerkship selection process is far more discreet and opaque. There is no public record of who applies, who is granted interviews, or the offers they receive (there is a norm, however, that applicants accept their first offer from a Justice 64 See Ditslear & Baum, Selection of Law Clerks, supra note 19, at 870 & n.1 (referencing work by John Greenya identifying this norm). ). Thus, while we observe the universe of successful applicants to the Court, we cannot observe unsuccessful applicants.

To better understand, we consider a forensic, inferential approach to understanding the clerkship selection process through the lens of a single school: Harvard Law School. Harvard Law School was chosen for this study because it produces the most Court clerks, historically and during our period of analysis. This is in large part due to its long-standing prestige, but also because the number of annual graduates from Harvard’s J.D. program approximates that from Yale, Stanford, and Chicago combined. Harvard also reports recipients of its Latin honors. In its annual commencement catalog, 65 The Harvard University Archives kindly provided copies of the University’s commencement programs containing law school graduate information for the graduating classes of 1980 through 2020. Harvard lists each law graduate, along with any level of honors they received, as well as when and where each graduate received their undergraduate degree.

In total, this study observed 22,475 J.D. graduates for the period from 1980 through 2020 and examined two recurring themes: academic performance and educational pedigree. 66 We also recognize that these honors occur at graduation, whereas clerkships are often determined before graduation. This study provides strong evidence that Latin honors remains a valid measure on the premise that law school performance is an important criterion. See infra Table 7. Because students’ academic records are nonpublic, we rely on observable proxies of academic performance. By comparing those who became Court clerks with those who did not, we assume that credible (but unsuccessful) applicants share similar characteristics, such as performance during law school.

Table 4 reports Harvard’s designation of honors. Over our total period of interest—1980 through 2020—nearly half (49%) of students at Harvard graduated with some form of academic honors (i.e., cum laude or higher). This number would likely have been higher had the law school not changed its grading system, starting with the Class of 1999, and limited the fraction of students graduating with honors at 40%: 10% for magna or summa cum laude, and the next 30% for cum laude. 67 See Gregory S. Krauss, New HLS Grading System Reduces Honors Graduates by More Than Half, Harv. Crimson (June 10, 1999), https://www.thecrimson.com/article/1999/6/10/new-hls-grading-system-reduces-honors/ [https://perma.cc/T8JU-UT6S] (“Before the new system was implemented, grade inflation in the past three decades had resulted in the number of students receiving honors more than doubling. In 1972 about 35 percent of the graduating class received honors. By last year [1998], that number had climbed to 76 percent . . . .”); see also Elias J. Groll, HLS Clarifies Grading Changes, Harv. Crimson, (Apr. 21, 2009), https://www.thecrimson.com/article/2009/4/21/hls-clarifies-grading-changes-clarifying-the/ [https://perma.cc/GF7C-2WNQ] (“[The] student handbook will include a recommended grade distribution that encourages professors to award Honors to 37 percent of the class, Pass to 55 percent, and Low Pass to the remaining 8 percent.”). For the period from 1980 through 1998, over 60% of students graduated with some honors designation, and the largest plurality graduated cum laude. After the change (1999 through 2020), the graduation requirements reflected the caps on academic honors.

Table 4. Harvard Law School—Graduating Honors Designation

1980–2020

| Honors | Graduating Class (1980–1998) |

Graduating Class (1999–2020) |

All Graduating Classes (1980–2020) |

| No Honors | 40.1% | 59.9% | 51.0% |

| Cum Laude | 47.2% | 29.9% | 37.7% |

| Magna Cum Laude | 12.7% | 10.0% | 11.2% |

| Summa Cum Laude | 0.0% | 0.2% | 0.1% |

While Harvard Law School accepts students from over 200 universities and colleges, closer examination reveals that the majority of students come from a small number of schools. Table 5 identifies these schools. More than a third of Harvard law students graduated from one of the eight Ivy League universities. It accepted another 11% of its students from seven select national universities. Another 7% came from four select public universities. It accepted another 2% from three national liberal arts colleges. With the exception of the Ivy League, which defines its membership, we constructed the other categories, admittedly with some level of arbitrariness. These categories are not meant to be an exhaustive list of elite or highly selective schools—as it undoubtedly excludes a number of academically comparable schools—but simply to illustrate the point that a small number of undergraduate institutions (twenty-two) represent the majority of students who enroll at Harvard Law School.

Notably, among these select undergraduate institutions, Harvard Law draws over a fifth of its enrolled students from just three schools: Harvard (11%), Yale (6%), and Princeton (4%). Over time, however, the law school has drawn from a broader selection of schools. Prior to its grading change (1980 through 1998), 58% of enrolled students attended the 22 undergraduate institutions identified in Table 5; after the grade change (1999 through 2020), only 53% attended these same schools. There were likewise declines in the percentage of students from all Ivy League institutions (from 38% to 31%) and from Harvard, Yale, or Princeton in particular (from 25% to 19%).

Table 5. Harvard Law Students—Undergraduate Institutions

1980–2020

| Category | n | Percentage of All Students |

| Ivy League (8) | 7,873 | 34% |

| Brown, Columbia, Cornell, Dartmouth, Harvard, Yale, University of Pennsylvania, Princeton | ||

| Select National Universities (7) | 2,504 | 11% |

| Chicago, Duke, Georgetown, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Northwestern, Notre Dame, Stanford | ||

| Select Public Universities (4) | 1,676 | 7% |

| University of California at Berkeley, University of Michigan (Ann Arbor), University of Texas (Austin), University of Virginia | ||

| Select Liberal Arts Colleges (3) | 585 | 3% |

| Amherst, Swarthmore, Williams | ||

| All Other Undergraduate Institutions | 10,426 | 45% |

The data also reveal the relationships between undergraduate institution attended and performance during law school. Table 6 reports the distribution of honors, based on whether the student attended one of the aforementioned twenty-two undergraduate institutions. The numbers show that the modal outcome for students, regardless of their undergraduate institution, is to graduate without honors. That said, a higher percentage of students from the twenty-two schools graduated with honors, for each of the three levels (cum, magna, summa). Among students with undergraduate degrees from Harvard, Yale, or Princeton (not shown in Table 6), 42% graduated cum laude and 17% graduated magna cum laude.

Table 6. Honors Received at Harvard Law School

by Undergraduate Institution

1980–2020

| Undergraduate Schools Not Listed in Table 5 | Undergraduate Schools Listed in Table 5 | All Undergraduate Schools | |

| No Honors | 58.0% | 45.2% | 51.0% |

| n | 6,045 | 5,710 | 11,755 |

| Cum Laude | 33.8% | 41.0% | 37.7% |

| n | 3,519 | 5,177 | 8,696 |

| Magna Cum Laude | 8.2% | 13.7% | 11.2% |

| n | 855 | 1,713 | 2,592 |

| Summa Cum Laude | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.1% |

| n | 7 | 14 | 21 |

| Total | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% |

| n | 10,426 | 12,638 | 23,064 |

Based on these baseline differences and Harvard Law’s overall influence on Court clerkships, the question is not whether education at a select undergraduate school increases the odds of clerkship, but by how much?

When we examine the interplay of undergraduate education and law school honors, a recurring pattern emerges. Table 7 shows that among students graduating from Harvard Law with honors (whatever the level), those who attended one of the twenty-two undergraduate institutions were much more likely to receive a Court clerkship than their classmates who did not attend one these schools. The 8,696 cum laude graduates were over three times more likely to become Court clerks if they graduated from one of the twenty-two undergraduate schools than the others. Among magna cum laude graduates, the source of most Court clerks at Harvard Law, graduates from the twenty-two undergraduate institutions were 72% more likely to be chosen than their non-twenty-two school counterparts. Differences at both these levels of honors were statistically significant (p<0.01). For the remaining two categories—no honors and summa cum laude—the differences again favored graduates from the twenty-two schools but were not statistically significant, reflecting in part the vanishingly small odds of clerking on the Court in the absence of receiving honors, and the exceedingly high chances of clerking on the Court among those earning summa cum laude, the highest honors.

Table 7. Percentage of Harvard Law Students Receiving

Supreme Court Clerkships, by Undergraduate Education

and Academic Honors

1980–2020

| Undergraduate Schools Not Listed in Table 5 | Undergraduate Schools Listed in Table 5 | All Undergraduate Schools | |

| No Honors | 0.0% | 0.1% | 0.0% |

| n | 6,045 | 5,710 | 11,755 |

| Cum Laude | 0.2% | 0.6% | 0.4% |

| n | 3,519 | 5,177 | 8,696 |

| Magna Cum Laude | 7.4% | 12.8% | 11.0% |

| n | 855 | 1,737 | 2,592 |

| Summa Cum Laude | 100.0% | 78.6% | 85.7% |

| n | 7 | 14 | 21 |

| Total | 0.7% | 2.1% | 1.5% |

| n | 10,426 | 12,638 | 23,064 |

These aggregate differences in rates of Court clerkships across undergraduate education and law school performance have endured over this period. Table 8 reports the Court clerkship rate by decade, focusing on those graduating with honors designation (cum, magna, or summa). Among cum laude graduates, graduates from the twenty-two undergraduate institutions were on average three times more likely to receive a Court clerkship. For magna cum laude graduates, the advantage of attending one of the twenty-two schools was smaller: between 50% and 100%. These within-decade differences are also statistically significant. The differences between the handful of students graduating summa cum laude were smaller and not statistically significant.

Table 8. Percentage of Harvard Law School Students,

Receiving Supreme Court Clerkships, by Undergraduate

Education and Academic Honors by Decade

68

The Justice might be leaning on status as a marker of likely future success in the labor market. Loyal clerks go on to advocate for the Justice. For example, J. Harvie Wilkinson, former clerk for Justice Powell and Fourth Circuit judge, wrote: “Occasionally, the former clerk becomes something of a disciple of the Justice for whom he once worked, a knowledgeable and sympathetic interpreter of the Justice’s views and positions to the world outside.” Wilkinson, supra note 31, at 60–61; see also John C. Jeffries Jr., Justice Lewis F. Powell Jr.: A Biography 225 (1994) (noting how Justice Douglas could inspire “admiration . . . affection and fierce devotion” from his clerks, but also “absolute terror . . . at the thought of making a mistake”). The list of clerks who have written about their Justices could go on and on. See, e.g., Philip Kurland, Mr. Justice Frankfurter and the Constitution (1971); Paul A. Freund, Mr. Justice Brandeis: A Centennial Memoir, 70 Harv. L. Rev. 769, 775 (1957); Charles A. Reich, Mr. Justice Black and the Living Constitution, 76 Harv. L. Rev. 673, 674 (1963).

1980–2020

| 1980s | 1990s | 2000s | 2010s | Total | |

| Cum Laude | |||||

| Undergraduate Schools Not Listed in Table 5 | 0.2% | 0.3% | 0.2% | 0.2% | 0.2% |

| Undergraduate Schools Listed in Table 5 | 0.6% | 0.5% | 0.7% | 0.6% | 0.6% |

| Magna Cum Laude | |||||

| Undergraduate Schools Not Listed in Table 5 | 9.0% | 6.8% | 8.4% | 6.2% | 7.4% |

| Undergraduate Schools Listed in Table 5 | 13.3% | 10.0% | 18.3% | 10.6% | 12.8% |

| Summa Cum Laude | |||||

| Undergraduate Schools Not Listed in Table 5 | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | |

| Undergraduate Schools Listed in Table 5 | 100.0% | 100.0% | 72.7% | 78.6% | |

| Total (Cum, Magna, and Summa) | |||||

| Undergraduate Schools Not Listed in Table 5 | 0.8% | 0.9% | 0.7% | 0.7% | 0.7% |

| Undergraduate Schools Listed in Table 5 | 2.1% | 2.1% | 2.5% | 1.8% | 2.1% |

Table 9 breaks down the data a bit further, and it reveals an interaction between undergraduate institutions and law school performance. Table 9, like Table 7, presents the percentage of students graduating with honors selected for Supreme Court clerkships. Table 9, separates three universities—Harvard, Yale, and Princeton (HYP)—from the other nineteen schools listed in Table 5. This separate analysis shows a pattern. 69 Table 9 reports the rate of Court clerkships by undergraduate institution and academic honors. The difference here is that we separate out HYP from the other 19 select undergraduate institutions that originally composed the twenty-two undergraduate institutions. We compare these two groups’ Court clerkship rates with each other and with those who attended all other undergraduate institutions. A pattern emerges: The selection rate for Court clerkships is appreciably higher for HYP graduates than for students from the other nineteen selective institutions. HYP cum laude graduates were three times more likely to be chosen than cum laude graduates from other nineteen schools; HYP magna cum laude graduates are selected at a 50% higher rate than magna cum laude graduates from other schools. Both of these differences are statistically significant (p<0.01).

Equally notable, the difference in Court clerkship rates between the nineteen schools and other (non-HYP) institutions are relatively small and in most instances are not statistically significant. This breakdown suggests that Harvard, Yale, or Princeton undergraduate students’ high clerkship rates drive much of the effect of undergraduate institution on Court clerkships.

Table 9. Percentage of Harvard Law School Students Receiving Supreme Court Clerkships, by Undergraduate Education

(Including HYP) and Academic Honors

1980–2020

| Undergrad Schools Not Listed in Table 5 | Harvard-Yale-Princeton (HYP) Undergrad | Undergrad Schools Listed in Table 5, Excluding HYP | All Undergrad Schools | |

| No Honors | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.1% | 0.0% |

| n | 6,045 | 2,020 | 3,690 | 11,755 |

| Cum Laude | 0.2% | 1.0% | 0.3% | 0.4% |

| n | 3,519 | 2,061 | 3,116 | 8,696 |

| Magna Cum Laude | 7.4% | 15.6% | 10.2% | 11.0% |

| n | 855 | 841 | 896 | 2,592 |

| Summa Cum Laude | 100.0% | 100.0% | 72.7% | 85.7% |

| n | 7 | 3 | 11 | 21 |

| Total | 0.7% | 3.1% | 1.5% | 1.5% |

| n | 10,426 | 4,925 | 7,713 | 23,064 |

The data indicate that the Justices have a measure of bias toward a certain type of candidate in terms of education and selection for clerkship with a feeder judge. What’s more, the Justices often make their hiring decisions before the applicant has worked for the feeder judge at the lower court. 70 See, e.g., Bossert, supra note 9 (“[S]ome clerks . . . have had their high court interviews before they begin clerking for anyone else, so their performance in circuit court chambers cannot be evaluated by justices who interview early.”). This is strange as the Justice has no information about how the applicant performed with the feeder. Additionally, the Supreme Court Justice making their hiring decision has all the same information that the lower court judge would have had, plus information from an additional year of grades and references in law school. So, what is selection by a feeder judge adding to the equation such that it makes the candidate more attractive? 71 Historically, Court clerks held their lower court and Court clerkships consecutively and immediately after law school. In recent years, however, some Court clerks have held multiple lower court clerkships prior to their Supreme Court clerkship. See Derek T. Muller, Federal Judicial Clerkship Report of Recent Law School Graduates 12 (2020 ed.), https://ssrn.com/abrstract=3203644 [https://perma.cc/RG6R-EJM5]. If a clerk holds a non-clerkship position between their lower court clerkship and their Court clerkship, the hiring Justice could ask the feeder judge for information about the clerk. The feeder would presumably be able to provide useful comparative information about this applicant versus others from the same chambers who ended up clerking on the Court.

One possibility is that these feeder judges are especially skilled at picking clerks who are suited for Supreme Court clerkships. Or maybe feeder judges provide superior training. We do not, however, have reason to think that any of the feeders invest especially in clerk selection or training. 72 Cf. Wald, supra note 30, at 153–54 (arguing that judges benefit from exceptional clerks and that judges may use their reputation as “feeders” to recruit the most qualified clerks). A related possibility, for which there is some evidence, is that the feeders screen for “ideological allies” for the Justice. 73 See Baum & Ditslear, Clerkships and “Feeder” Judges, supra note 10, at 33–35. Baum and Ditslear hypothesized that Justices look to “ideological allies” on lower courts because Justices who are engaged in an ideological battle on the court “will give a high priority to ensuring that their clerks are willing to follow their lead.” See Ditslear & Baum, Selection of Law Clerks, supra note 19, at 872; cf. William E. Nelson, Harvey Rishikof, I. Scott Messinger & Michael Jo, The Supreme Court Clerkship and the Polarization of the Court: Can the Polarization Be Fixed? 13 Green Bag Second Series 59, 66 (2009) (suggesting that the ideological matching might reflect and fuel judicial polarization). Yet another possibility is that the Justices are selecting for status (such as education at Harvard, Yale, or Stanford) that, in turn, might predict future career success. One might imagine that Justices get value from the success of their former clerks, especially if that success then translates into the greater glory of the Justice. The reality is that we do not know which of these dynamics are at play.

One way to examine the status aspect of this question is to dig deeper into the credentials of those who do receive the clerkships. Do they bring more meaningful qualifications to the table? Given a strong performance in law school, it should not matter whether applicants attended a high-status or a low-status undergraduate college or university. If anything, a person from a less prestigious undergraduate school who made it to Harvard Law and outperformed their classmates who went to Princeton may be more deserving of a Court clerkship, given hurdles they overcame. But Justices who care about status may still prefer the Princeton graduate.

II. Life After Clerkship: Labor Market Participation of Clerks

A Supreme Court clerkship is coveted not only as a substantial prize but also as a meaningful prospect for future endeavors. Justice Brandeis and Professor—later Justice—Frankfurter built out the clerkship system precisely for that reason.

74

See Nelson et al., The Liberal Tradition, supra note 6, at 1756–61.

Brandeis’s design was to have the Court develop the next generation of legal academics, contributing to the development of the law.

75

See Philippa Strum, Brandeis: Beyond Progressivism 66, 70 (1993) (describing interactions between Brandeis and his clerks); Philippa Strum, Louis D. Brandeis: Justice for the People 359 (1984) (detailing Justice Brandeis’s efforts to funnel his clerks into

legal academia). For direct evidence of Brandeis’s vision, see Letter from Louis D. Brandeis to Felix Frankfurter (Jan. 28, 1928), in 5 Letters of Louis D. Brandeis 319, 320 (Melvin I. Urofsky & David Levy eds., 1978) (requesting Frankfurter, who selected Brandeis’s clerks, “to take some one whom there is reason to believe will become a law teacher” if possible).

The only study of post-clerkship careers concludes that Brandeis’s vision “endured for some three-quarters of a century,” from 1916 to 1989, and “became a norm for Justices and former clerks of all political persuasions.”

76

Nelson et al., The Liberal Tradition, supra note 6, at 1769 (charting the development of Brandeis’s model for clerkships, which began with his appointment to the Supreme Court in 1916 and eventually became the norm until around 1990, when things began to change).

But do the same characteristics that increase the odds of a Court clerkship also contribute to success in the post-clerkship labor market? Attorneys William Nelson, Harvey Rishikof, Scott Messinger, and Michael Jo’s historical legal study is not only the first such empirical study but also makes important contributions by identifying the range of initial post-clerkship jobs and how that range has changed over time. 77 Id. at 1753. Their project, however, did not include the clerks’ own background in evaluating their subsequent employment. It also focused on testing the hypothesis that the Brandeis model of clerkships as an academic pipeline failed as the Court became more conservative. We find that high-status educational background—both undergraduate and law school—looms large in the clerkship process. Do these prior status differentials continue to matter after one acquires the highest status bauble, the Supreme Court clerkship? Or is the clerkship of such value in the post-clerkship employment market that it scrubs away all prior status differentials?