I. In the Beginning

On Monday, June 5, 1972, a future Columbia Law student was born in Edison, New Jersey. The newborn’s mother experienced a healthy pregnancy, working as a high school math teacher at Edison High School, right up to the day of her death on June 5, 1972. Following in the Jewish tradition her internment took place the next day, June 6th. Edison High School closed in her honor.

A few days later, as Jason Paul Wiesenfeld (the newborn infant) was ready to go home from the hospital, I, without my wife, Paula Wiesenfeld, was prepared to take him home and take good care of him.

Paula and I, both eager to achieve leadership positions, had been working hard toward our goals: Paula continuing to study for her Ph.D. in education, and I, building a cutting-edge consulting company. My small, independent consulting firm was in the start-up phase of becoming a computer-based consulting company.

Shortly after my wife passed, I, along with my father, visited the local Social Security office in New Brunswick, New Jersey. I applied for the death benefit on behalf of my late wife (a benefit for the child of an insured parent who has passed) and the “Mother’s Insurance Benefit” on my own behalf (a benefit for the surviving mother, with children in her care, of a deceased insured husband). No benefit existed that could be called the “Father’s Insurance Benefit.” And so as it happened, I was denied the “Mother’s Insurance Benefit.”

I spent some time thinking about why I was not receiving an insurance benefit. There was something wrong here.

My late wife, Paula, had to pay into the Social Security System, without receiving any coverage for a Father’s Insurance Benefit. A similarly situated male—teaching and earning the same income as Paula, as well as paying the same amount into the Social Security System—was covered for a “Mother’s Insurance Benefit.” Wasn’t Paula’s income diminished without receiving the coverage? In the age of the Equal Rights Amendment wasn’t this an inequality? This went against the equal-pay-for-equal-work tenet.

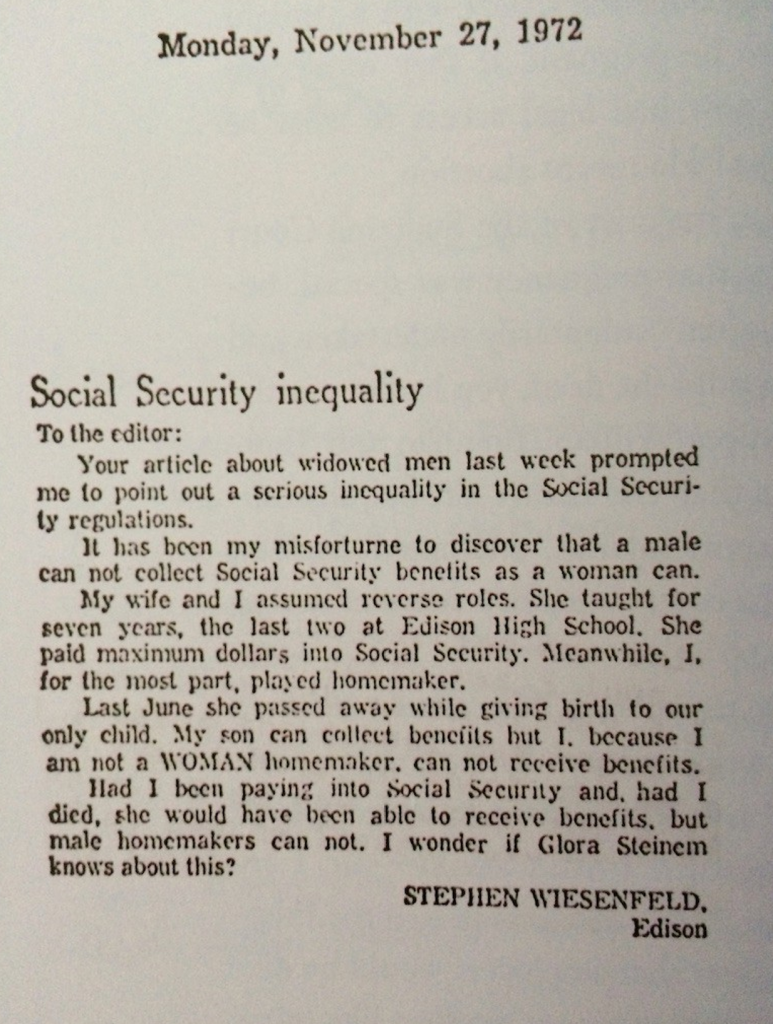

Several months passed by. I made little progress, and still had no path moving toward righting this wrong. It was November 1972 when my local newspaper, the New Brunswick Home News, carried a wire service article about lifestyles. Still desiring to move forward, I thought that a letter to the editor may produce some favorable results. I wrote a response to the story about lifestyles and described my condition. Here is what I wrote:

Phyllis Zatlin Boring, a Spanish professor at Rutgers University in New Brunswick, responded to my letter the same day she read it in the newspaper: November 27, 1972. “Waiting for legislative reform,” she wrote, “can take a long time. In reading your letter the thought occurred to me that a legal test of the Social Security Law might be faster.” She said she could put me in touch with a friend at the ACLU, and they could handle my case while using a volunteer lawyer. Phyllis did not mention that her friend who had recently taught at Rutgers University as a law professor was Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

Ruth Bader Ginsburg, who had just become head of the Women’s Rights Project at the ACLU.

I responded favorably to Phyllis’s letter and on December 26th, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, attorney at law, called me on the phone. I was flattered and was duly impressed with her, and by what she told me. She pointed out that there would be no need for me to invest any time, by appearing in court or otherwise, except for a trip to Newark to give a legal deposition. I was very impressed that the ACLU would raise the cash to run the case and that I would have to pay no expense related to my case. Ruth Bader Ginsburg also cautioned me that it was likely that I would not gain anything, either. Ruth would soon understand that I could not possibly be doing it for the money. Any job I would have would outdistance the social security benefit by far.

I knew that even the small Social Security benefit, along with the child’s benefit—adding in some savings and help from my parents—would give me enough, living frugally, to actually stay home and raise Jason. But more importantly, the inequality of the law made no sense to me. I was ready and eager to be a father and to raise Jason until he was old enough to come home from school, let himself in the house, and be alone for about two hours. My late wife, Paula, and I had talked about who could be where, and when. Paula, remember, wanted to continue to teach and go to school. I could arrange my schedule to accommodate Paula’s path. I was also aware that we were attempting to bring the suit as a class action, so—if successful—other similarly situated men would be able to take advantage of the benefit. 1 The district court, however, ultimately denied class certification. Wiesenfeld v. Sec’y of Health, Educ. & Welfare, 367 F. Supp. 981, 986–87 (D.N.J. 1973).

The phone conversation continued with Ruth Bader Ginsburg describing to me that, no matter who won in the district court, the loser would appeal directly to the United States Supreme Court. They would skip the court of appeals and go to the Supreme Court because the case contained undisputed facts and a constitutional issue. Ruth told me that this was a rare combination.

When the phone call ended, Ruth Bader Ginsburg probably sat back and took a deep breath. She had found the case that she had been waiting years for. As the head of the Constitutional Law Center in Philadelphia, Jeffrey Rosen has said, “At the ACLU she would also take on the case that would define her career.” 2 Ruth Bader Ginsburg: A Tribute in Words and Music, at 25:23 (NBCUniversal 2020). Ruth Bader Ginsburg is quoted as saying, “‘[I]f ever there was a case to attract suspect classification for sex lines in the law,’ Wiesenfeld was that case. Legally, it had everything.” 3 Fred Strebeigh, Equal: Women Reshape the Law 65 (2009).

Mary Elizabeth Freeman, who helped write the brief for the Supreme Court, said many years afterward that the case was “illustrative of what Ruth has been saying her whole life, about children and parents and childcare. She has always emphasized the need to bring fathers into the picture and make them fully responsible. And here Stephen was stepping up to the plate and doing it.” 4 Id. at 68 (internal quotation marks omitted) (quoting Mary Elizabeth Freeman).

Also, many years later, Mary Elizabeth Freeman was again quoted as saying:

[T]o pick a man whose wife died in childbirth, something that doesn’t happen a lot in the latter part of the twentieth century, with a baby—a child in arms that has, as its only parent left, a father who wants to take care of his kid! I mean, widows and orphans—you can’t get any better than that! 5 Id. at 67 (internal quotation marks omitted) (quoting Mary Elizabeth Freeman).

II. The Filing

The first filing came during the last week in February 1973. It would not reach the first court appearance until June, but it became newsworthy immediately. The story started appearing in newspapers and I was being interviewed as journalists wanted to know more.

I had no idea that this case would become so popular with the press without ever being in a courtroom. I did not immediately grasp how important it was. What I was embarking upon would define RBG’s career as well as change the way people thought about equality. I would soon learn more, when nationally known journalists, such as Bill Moyers from PBS, would come to Edison, New Jersey, to visit and interview me at home, bringing with him a four-person film crew.

III. The Three-Judge Panel in Federal Court

The case was heard first in front of a three-judge panel in federal court in Trenton, New Jersey. I met up with Ruth and an associate on the ride from New York City to Trenton. It was my understanding that the United States Attorney who was presenting his side of the case had asked for a dismissal due to the fact that I was working with a salary that placed me in a position to be ineligible for any Social Security benefit. This was a sudden and unexpected request that drained all the air from my lungs. I recall a moment that the three judges whispered among themselves and then asked the U.S. Attorney to continue.

I suspected that the judges felt that I could become unemployed again and then bring the case again. From conversations with Ruth, I learned that American law ran strongly in favor of gender stereotypes that men work and women care for the home and raise the children. Men simply don’t stay home and raise children.

The defense brought up a second reason in an attempt to have the case dismissed. They felt it was unlikely that the benefit I might receive would reach the court’s minimum remedy of ten thousand dollars. I recall the judges again wanted the case to continue. It was June of 1973. 6 More recently, sometime in the last few years, I asked Ruth whether the judges would have dismissed the case if I hadn’t adjusted my income to appear in that courtroom. She declined to speculate, and offered only that she did not know how they would rule.

At home, I became concerned about my current earnings disqualifying me from not only receiving the benefit but even from having the case move forward from this point. All that work and preparation would be allocated to the garbage heap. I decided that I would intentionally lose my job and alter my career plans to position myself so the case could continue.

I did not discuss my plan with Ruth or anyone else. I told no one of my plan. I knew no one would agree with me. I was leaving a very lucrative job and a promising future to stay home and raise Jason, while receiving a Social Security benefit of just $206 per month. But I was, and still am, very principled. What I was doing to favor equal treatment for men and women, according to law, had reached a new levelof importance to me.

I would find some way to better control my income so as not to earn more than $200 per month. I needed something where I could easily control my time as well, so I could spend the necessary time with my new son, Jason. I decided that I could manage these two goals by opening and operating a retail store in my neighborhood. I then added the requirement that I had to sell a high-profit item, or items that I could move out quickly.

After much research, I decided upon my temporary path. In September 1973, I opened a bicycle shop in Highland Park, near where Jason and I made our home. I knew next to nothing about bicycles, but this was not about the product; it was about the process and the goal. I knew this was an excellent choice, as the world was only a month or so away from the first oil embargo of the 1970s that created long lines at automobile fueling stations. What luck? Not all luck, I was well-educated, had an MBA, and was an avid reader of newspapers. I had carefully studied what was happening in the Middle East.

The bicycle shop was located across the street from a gas station. People were leaving their cars home and using bicycles again. The shop did well; I chose to sell a bicycle that a popular ratings magazine had just rated number one. Highland Park was located across the river from Rutgers University, and the upscale town held the homes of many wealthy people, so the bicycle shop made money.

I would draw only $200 per month, keeping in mind the limits placed on me to keep my case active. The remainder of the available money went into buying and building a huge inventory of bicycles. I knew that after the Supreme Court ruled, I would sell the store with its inventory of bicycles.

Meanwhile, the district court was holding the case in abeyance. It was months later, in December 1973, that a ruling was finally released. It contained a two-page essay on the powerful argument, made by the government, for dismissal. The salary that I had previously been earning was too much for Social Security to offer me any benefit. My previous earnings could have ended the case at that point. My feelings were right on target—leaving my job allowed the court to issue a 3-0 favorable ruling for my case. 7 Wiesenfeld v. Sec’y of Health, Educ. & Welfare, 367 F. Supp. 981, 985–96 (D.N.J. 1973) (“It would be a futile act for us to dismiss the complaint for lack of jurisdiction on the ground that the possibility of plaintiff losing his job was too speculative when apparently he is now unemployed.”).

IV. The United States Supreme Court

The Solicitor General at the time was Robert Bork. He rose to Acting Attorney General for a short period during the “Saturday Night Massacre.” 8 See Kenneth B. Noble, Bork Irked by Emphasis on His Role in Watergate, N.Y. Times, July 2, 1987, at A22, https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1987/07/02/029587.html?pageNumber=22 (on file with the Columbia Law Review). His two predecessors had resigned, but Bork had no problem firing Archibald Cox. After the dirty work, a new Attorney General was appointed and Bork returned to his job as Solicitor General. It was February 1974 when Robert Bork decided he did not agree with the lower court’s ruling in the Wiesenfeld case and notified the Supreme Court that he intended to appeal. Just as Ruth Bader Ginsburg predicted he would.

The government filed its appeal, and Ruth prepared to present the case before the United States Supreme Court.

I had attended the presentation at the district court, so I also joined Ruth at the Supreme Court. The night before we were to appear, Ruth called me and discussed her strategy for her presentation. Ruth Bader Ginsburg was confident that, with Justice Douglas out ill, she would get a 4-4 split and therefore an affirmation of the lower court’s decision. But one can always use a bit of extra insurance. She said she would aim her argument at Justice Stewart by using his words from his recent past writings. She wanted to get him to decide, in her favor, giving her a 5-3 win. An honorable strategy.

I met up with Ruth in time to have lunch before the case was scheduled at the Court. She didn’t eat much, as was her usual manner before presenting a case. When we walked into the courtroom, as the one o’clock hour approached, she sat me down at the counsel table with her. She had never before, at the Supreme Court, had her client sit at the table with her. She would never do it again. I was the only client that she sat directly beside her at the counsel table. I found out later that she wanted the Justices to see a male in front of them and hoped that the all-male Court would identify with me. She wanted the Court to understand that this was reality, that “this sort of sex stereotyping hurt many people, everyday people, people like Stephen Wiesenfeld.” 9 Strebeigh, supra note 3, at 72 (internal quotation marks omitted) (quoting Ruth Bader Ginsburg).

And here one comes upon Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s response to Robert Bork’s filing at the court. She decided to place the case of the deceased Paula Wiesenfeld first. Her argument was powerful, and she used the same one when giving oral argument before the Court in January 1975. She wrote and later spoke:

[Paula Wiesenfeld] contributed to Social Security on precisely the same basis as an insured male individual. Upon her death, however, her family received fewer benefits than those paid to similarly situated families of male breadwinners. The sole reason for the differential was Paula Wiesenfeld’s sex. As a breadwinning woman, she was treated equally for Social Security contribution purposes, but unequally for the purpose of determining family benefits due under her account. 10 Id. at 71–72 (quoting Brief for Appellee at 10, Weinberger v. Wiesenfeld, 420 U.S. 636 (1975) (No. 73-1892), 1974 WL 186057).

During oral argument she expanded what the brief contained, pointing out that because “the deceased worker is female,” the family was subject “to a 50 percent discount.” 11 Id. at 72 (internal quotation marks omitted) (quoting Oral Argument at 25:59, Wiesenfeld, 420 U.S. 636 (No. 73-1892), https://www.oyez.org/cases/1974/73-1892 (on file with the Columbia Law Review)). She was pointing out that the law tended to classify people according to their sex. People are better classified according to their work. Continuing, she told the Justices:

Paula Wiesenfeld, in fact the principal wage earner, is treated as though her years of work were only of secondary value to her family. Stephen Wiesenfeld, in fact the nurturing parent, is treated as though he did not perform that function. And Jason Paul, a motherless infant with a father able and willing to provide care for him personally, is treated as an infant not entitled to the personal care of his sole surviving parent. 12 Id. (internal quotation marks omitted) (quoting Oral Argument at 32:47, Wiesenfeld, 420 U.S. 636 (No. 73-1892), https://www.oyez.org/cases/1974/73-1892 (on file with the Columbia Law Review)).

She argued the case before the Court using the term “double-edged sword,” 13 Oral Argument at 32:30, Wiesenfeld, 420 U.S. 636 (No. 73-1892), https://www.oyez.org/cases/1974/73-1892 (on file with the Columbia Law Review). a term that soon would become well known. Her point was that the insurance benefit could be given to the family of a nonworking mother while at the same time would take away the benefit from a working mother who had died. The law, as written, devalues the labor of Paula Wiesenfeld. Ruth Bader Ginsburg wrote in her brief that this “presents a classic example of the double-edged discrimination characteristic of laws that chivalrous gentlemen, sitting in all-male chambers, misconceive as a favor to the ladies.” 14 Brief for Appellee at 23, Wiesenfeld, 420 U.S. 636 (No. 73-1892), 1974 WL 186057. RBG loved to use these types of “zingers” as she called them.

She intended this type of terminology to point out that these Justices, if they voted against her, were living well into the past. They would be in favor of collecting Paula Wiesenfeld’s money and then, because she was a woman, giving nothing back.

V. The Decision

Two months later the decision was announced and RBG, who was driving alone in her car, heard the news on the radio and stopped at a roadside phone booth (remember, this was before cell phones) to call me. I had already heard the news but could not answer the question she was most anxious about. That is, how the Justices voted. The victory was major as the Justices all voted with her. A unanimous decision. 15 Wiesenfeld, 420 U.S. 636. Rehnquist? Yes! Even Justice Rehnquist—who agreed with the decision but wrote his own opinion; he was the only Justice to concur for the reason that he thought it was discrimination against the baby. 16 Id. at 655 (Rehnquist, J., concurring in the judgment). Justice Powell, joined by Chief Justice Burger, also wrote a separate opinion but did so merely to “identify the impermissible [sex] discrimination . . . somewhat more narrowly than the [majority].” Id. at 664–65 (Powell, J., concurring).

The following month, the Ginsburgs held a victory party at their home on Manhattan’s Upper East Side. Jason and I showed up and Jason was entertained by Ruth’s children Jane (who now teaches at Columbia Law) and James.

The Social Security award, now two years later, had risen to $248 per month. I stretched it out and managed to stay with Jason, as initially planned, until he was able to come home from school, let himself in, and be alone for an hour or two. Jason was then nine years old and in September 1981, I once again opened my computer consulting and software-design business. I earned enough money that by the end of that year (a little more than three months) I had to pay back all the social security money I had received for the entire year!

VI. Jason Goes to Columbia Law School

In 1993, the year Ruth Bader Ginsburg was nominated for the Supreme Court, Jason was entering his senior year at the University of Florida and contemplating going to law school. In July 1993, on the first day of Ruth’s advice and consent hearings, she was being interviewed by Senator Edward Kennedy. They spoke about the case, now widely known as Weinberger v. Wiesenfeld. After Ruth’s explanation, Senator Kennedy mentioned that Ruth still stayed in touch with my family. She affirmed and added that Jason was in his last year of college and was planning to apply to law school.

This was on national television and compelled Jason to follow through and apply to law school. One of the schools Jason applied to was Columbia Law School. On Friday, the last day of the hearings, I was the last person to testify on Ruth’s behalf. Ruth’s confirmation was swift, and she was present at the Court on the first Monday in October in 1993.

Ruth was invited to participate in a panel discussion before the Columbia Law students in December 1993. It was broadcast nationally on PBS. The discussion eventually came to RBG’s favorite case. At the end of the conversation about the case, Ruth again mentioned that Jason was in his last year of college and was applying to law schools. She paused and then added that his number one choice was Columbia Law School. The audience of Columbia Law students applauded and cheered happily at the idea. Jason’s future had been decided on national television, and he was now compelled to attend Columbia Law School.

An item of synchronicity: When Ruth attended Columbia Law, her commercial law professor was Professor Farnsworth. Jason studied contracts under the same gentleman almost forty years later.

VII. The Lasting Friendship

In 1998, Ruth came to South Florida to perform the wedding ceremony for Carrie and Jason. She brought her granddaughter Clara and when we had free time on Sunday afternoon before the wedding, Ruth and I, along with my sister’s family, Clara, and my grandniece Sabrina, went to the zoo.

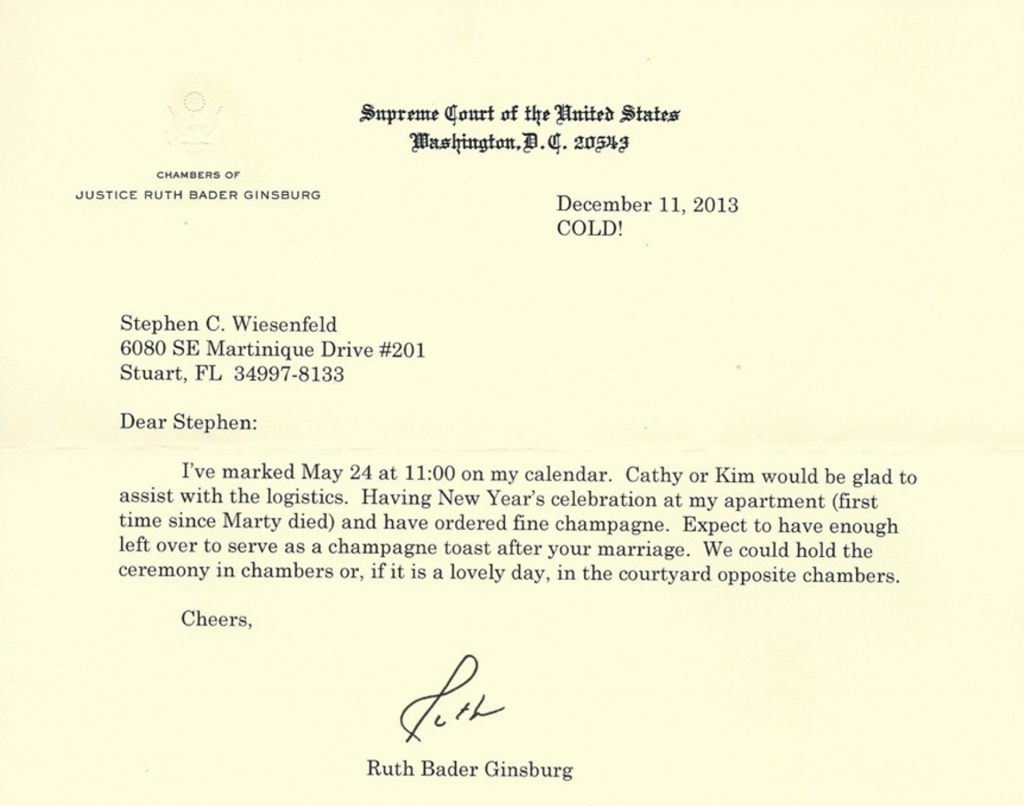

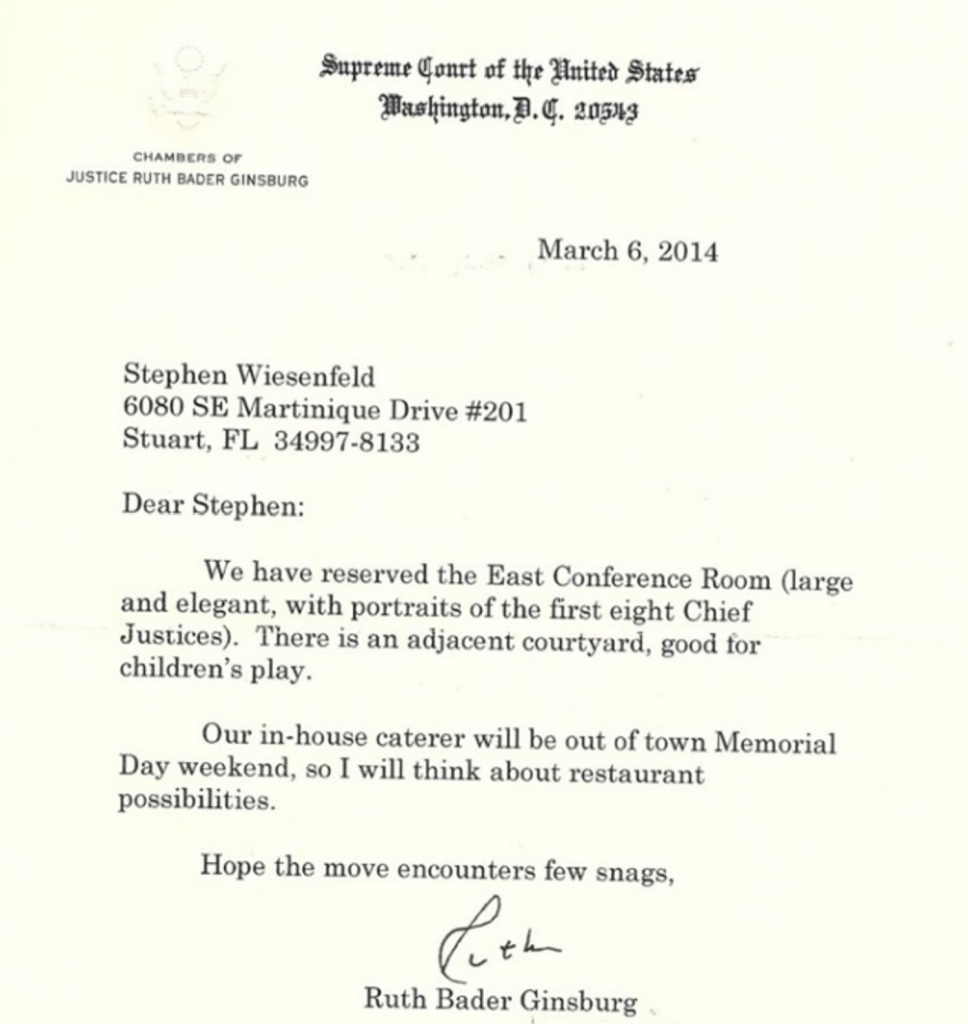

During the weekend of May 24, 2014, Ruth performed Elaine’s and my wedding in the East Conference Room of the Supreme Court. She wanted to do it in chambers, but there were more guests than the room would accommodate.

Following the wedding ceremony, we all went back to Ruth’s chambers and enjoyed a champagne toast that she had prepared. After we visited in her chambers, we all went to the National Museum of Art for our wedding lunch.

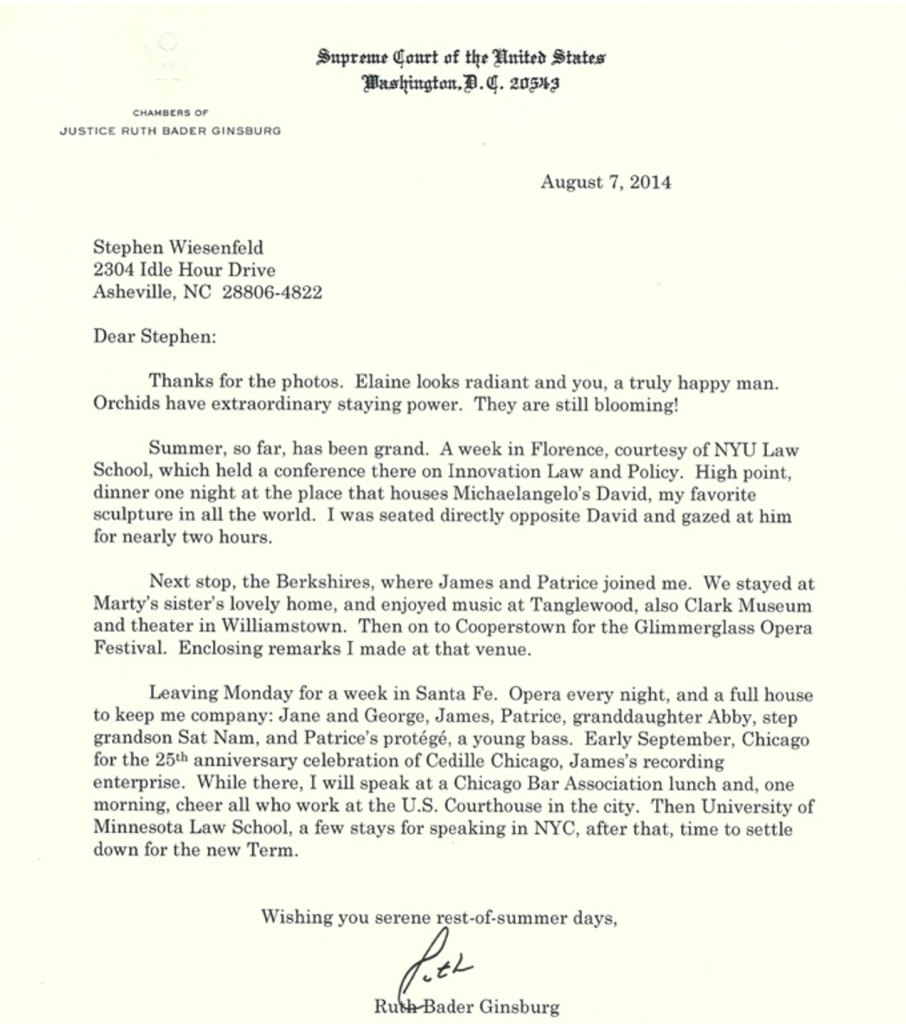

Orchids had been placed on the tables and, being that no one was local, Ruth was happy to take all of them home with her. After lunch, Ruth’s security detail helped carry them to the car.

In October 2007, Ruth and her husband, Marty, visited me in Asheville, North Carolina. I’ve had a summer home in Asheville since 1995. I had been telling Ruth so many good things about Asheville that when the state bar association invited Ruth to participate in a conference in North Carolina—and if she would come, she would get the honor of picking the venue—her first choice was natural: Asheville. During a free afternoon Ruth, Marty, and I did a private tour at the famous Biltmore Estate with Mimi, the wife of a Vanderbilt descendant.

During the tour, I commented to Marty that I thought Marty would be wearing a tie and jacket. You see in the photo that I am, but Marty is not. Marty invited me to take off my tie and be comfortable. So I did.

After the Biltmore Estate, we exited to our own quarters to rest and planned to meet at Vincenzo’s Italian Restaurant, downtown Asheville, for dinner.

I did not wear a tie. Marty had a jacket and tie. I immediately commented that now I was without tie and Marty was wearing one. Without hesitation Marty took his tie off and we had a good laugh.

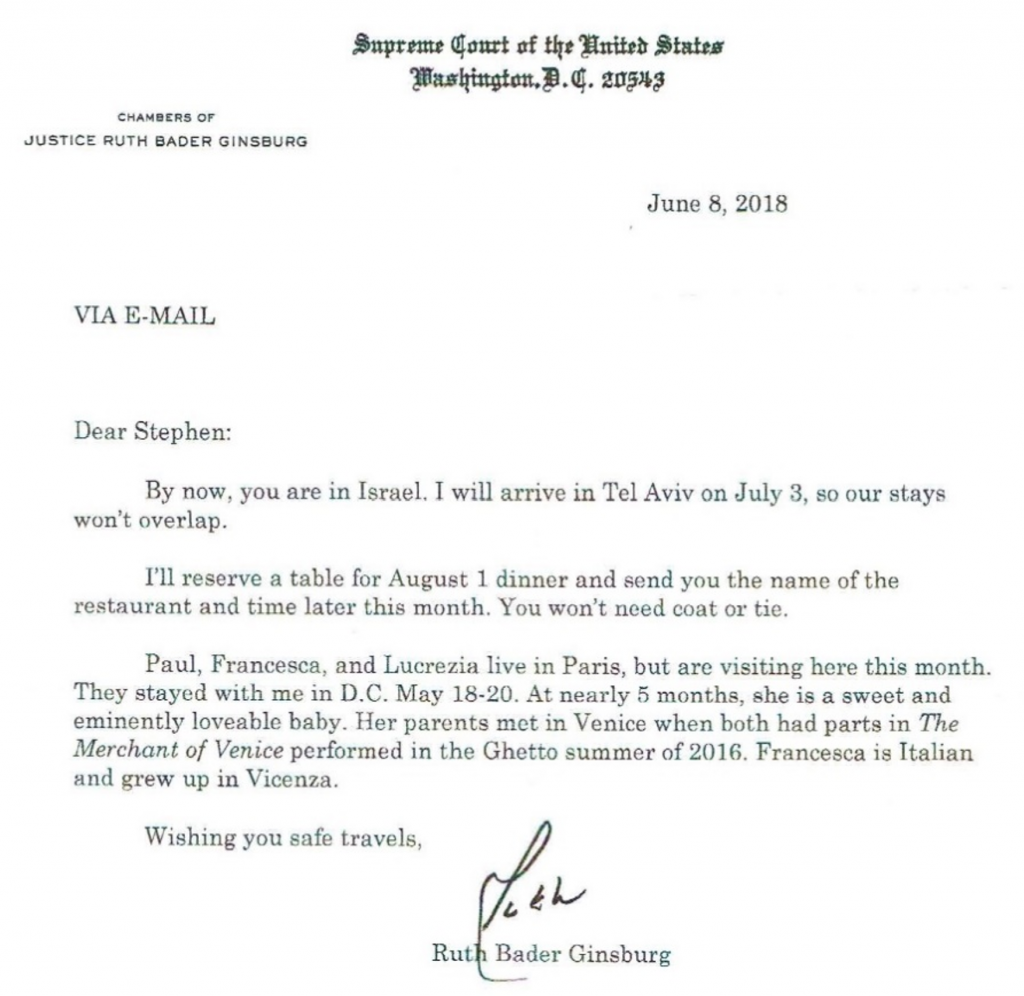

Eleven years later, Ruth recalled the fun and added a comment in the second line of the following letter. Ruth and I, with my wife, Elaine, were planning our time together while I was in Washington on August 1, 2018.

More than thirty years passed before my secret reason for leaving my lucrative job to keep the case alive was revealed. It wasn’t until 2005 that Ruth and I were each given the preliminary manuscript for a book that would be published in 2009. In the manuscript, we each had learned something about the other that was not known before. I learned that my case was the “first gender discrimination case that [Ruth] would control from start to finish.” 17 ebeigh, supra note 3, at 10. And for the first time, Ruth Bader Ginsburg found out that I gave up my planned future to see the case to completion.

Many have tagged Ruth Bader Ginsburg as a “women’s Libber.” Is she?

She approached life and work with these words: “We the people.” She believed in and fought for “justice for all.” She succeeded to a great extent. Attitudes toward the sexes are much different today than they were fifty years ago. As an example: Most job classifications that were single sex are now open to all.

It is important to remember the late RBG who brought me to the Supreme Court. She shifted the thinking of the conservative Burger Court. The Court was once steeped in hundreds of years of stereotyping men as breadwinners and women as homemakers. RBG liberated them from their chains and taught them how to approach gender-based discrimination. It took all of six years to accomplish it. Just amazing.

RBG’s death last year was a great global loss for all and a deeply personal one for me. She will be studied and missed by generations to come. I miss her!